Hello and thank you for reading the Little Detroit History Letter! I don’t know whether I am thrilled or terrified to share this letter with you today. First of all, it’s about trash. Secondly, it is only the beginning of a saga that spans literally a century. I will be telling it over a few installments, as I am very obsessed and it is a very long story. But I promise by the end of it you’ll never take your garbage for granted again. More soon!

-aeb

In the fall of 1860, Sylvester Larned purchased a storied old house, on an old French farm, on the old River Road that once encircled Fort Detroit. Sylvester’s father Charles had fought — and failed — to defend the fort from surrender in the War of 1812. After the war, Charles settled in Detroit and practiced law. Charles died in 1834, in a devastating cholera epidemic that killed about a seventh of the city’s population. Sylvester was 14 years old.

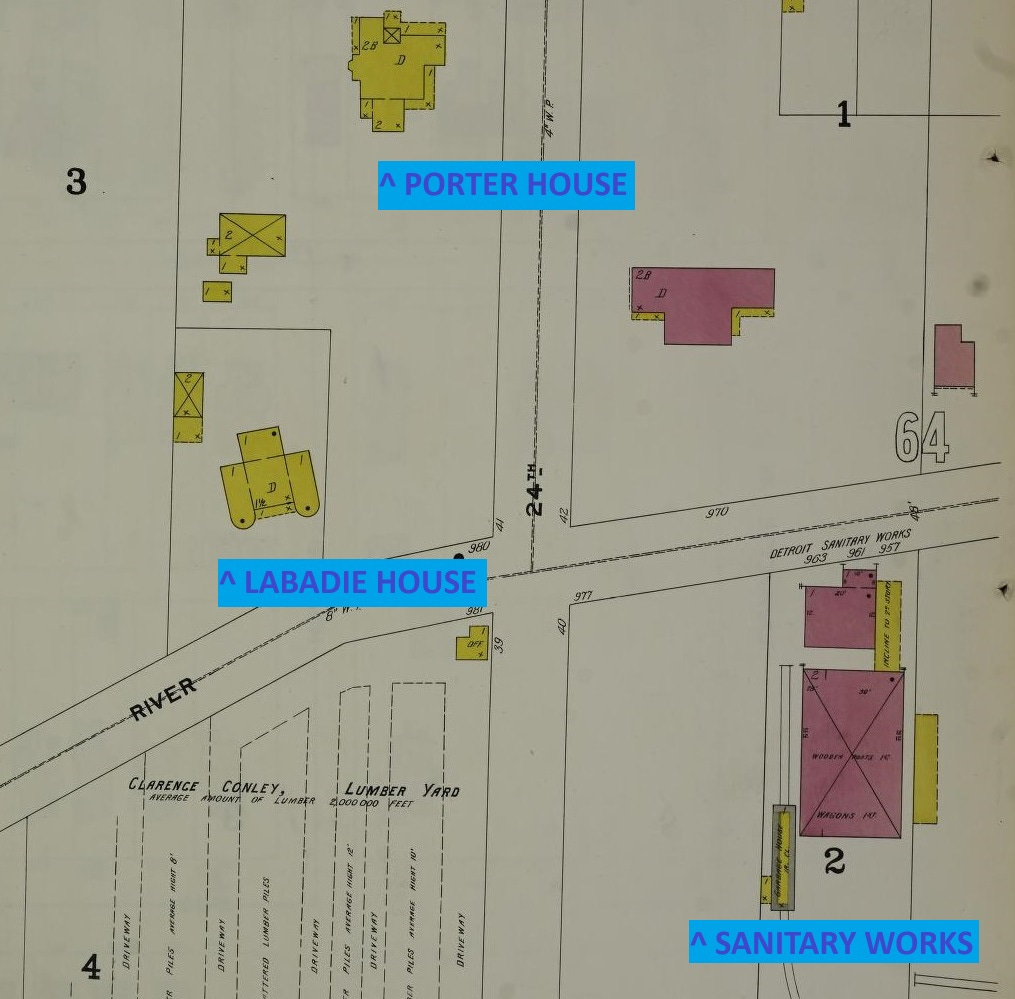

The same cholera outbreak also killed the man who once owned the old French farm and built the old house, George Bryan Porter, governor of the Michigan territory. The land Porter left behind became known as the Porter Farm, but by the time Sylvester bought the house — sold at auction by order of a Circuit Court judge to settle a debt — the land had been subdivided. What Sylvester bought was Porter’s house and a portion of the old Porter Farm between Fort Street and the River Road, west of 24th Street.

Photo: The old Gov. Porter House at 24th and River Road, where Sylvester Larned lived for 25 years. From the Burton Historical Collection, Detroit Public Library.

On another part of the Porter Farm was another historic building, an old French cottage called the Labadie House, which I have been studying, slowly, since Dan Austin told me about it over a year ago. This was supposed to be a story about the Labadie House, but — sorry Dan! — there’s been a change of plans.1

Now it is a story about the garbage.

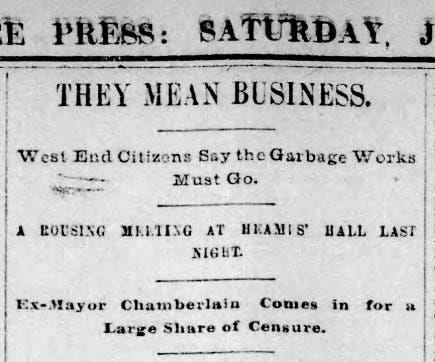

The headline that led me down the rabbit hole. Extremely meme-able, please use freely. From the Detroit Free Press, June 1, 1892.

Things had changed a lot along the River Road even by the time Sylvester Larned bought the Porter House in 1860. Detroit’s riverfront had become the hub of an increasingly industrial economy, its docks shipping out lumber, flour, stone, furs, leather, and even the ships that carried them.

Those businesses grew over the 25 years that Larned lived on the river, and more came along: lime kilns, a soap factory, a coal dock, a pork house, and the city gas works. For 25 years, Larned lived with all of the noise and smell and traffic those operations created. Until, in 1889, one more business opened up in the neighborhood.

It was called the Detroit Sanitary Works. It was a garbage plant. And for Sylvester Larned, it was the last straw.

A brief history of Detroit’s trash

For 150 years or so, Detroit residents had handled their trash on their own. Householders fed their food scraps to their pigs. Restaurants and hotels sold their garbage to farmers for feed and fertilizer. Manufacturers conserved materials and repurposed or sold their scraps. And, sure, people just threw their trash in parks and vacant lots, dumped it in the river, or burned it in their backyards.2

But as Detroit became less agrarian, more industrial, and a lot more densely populated, trash became more of a problem. The city’s health department tried to control it through various ordinances that spelled out what residents were not to do with their garbage: throw it in the river, toss it in the alley, dump it anywhere within city limits. But no one told residents what to do with it. Eventually, many people just became trash bandits: “Large quantities of putrescible matter are clandestinely deposited on vacant lots in the outskirts of the city, rotting, stinking and infecting the air in many neighborhoods,” the Detroit Board of Health wrote in an 1884 letter to the Common Council.

A bucolic view of Bloody Run at Elmwood Cemetery. On either side of the cemetery’s gates, Bloody Run valley was a “ditch” that was filled with so much garbage that the city’s health department hired its own detectives to try to deter illegal dumping in its waters.

The health department wanted the Council to take action, but no one was really sure exactly what action to take, and so the “garbage problem” was debated for years. Dr. O.W. Wight, who led the health department in the 1880s, was an advocate of a sanctioned municipal system for dumping waste into the river, in which residents would bring their trash to city-owned scows that would then offload the trash into the water. (Wight was adamant that there was no evidence that this would have any harmful effects: “The fact is the fishes in the river will not be killed by garbage but will eat it all up,” he told a reporter when questioned about the environmental impact of his trash plan. “This is not theory. It has been proved by long experience.”) Other city leaders pushed for burying the garbage, incinerating it, or “reducing” it to saleable byproducts through a process known as the Merz method.

In 1889, the city of Detroit entered into a contract with one of these Merz-style “reduction” facilities — the Detroit Sanitary Works, a company led by former mayor Marvin H. Chamberlain. Under the terms of the contract, the Sanitary Works would collect all of the city’s animal and vegetable waste for $35,000 annually.3 The garbage would then be “treated chemically and reduced to fat and fertilizers.”

It was Detroit’s first try at the municipal collection and disposal of trash. The Sanitary Works’ state-of-the-art new garbage factory opened for business on January 20, 1890, at the foot of 24th Street on the Detroit River.

A clip of the 1897 Sanborn Fire Insurance Co. map of 24th and River Road, with key locations in the story labeled — the Porter House where Col. Larned lived, the Labadie House that was supposed to be the oldest in Detroit, and the Sanitary Works.

That day, a Free Press reporter toured the works and reported with awe that it didn’t smell bad at all. Chamberlain showed the reporter a three-story factory system for sorting trash, steaming it (?) dehydrating it (??), and pressing out its oils (???), thereby transforming vats of dead fish and rotten cabbages into a tidy pile of unscented brown dust.4

Of course, the reporter did not return weeks later to see the trash start to pile up and rot. He did not stand around sniffing the riverfront as the backlogged garbage was burned. Also, the trash probably didn’t smell too bad in January! By June, hundreds of queasy neighbors of the Sanitary Works were complaining that not only did the garbage works smell horrible, but they were starting to get physically sick.

A West Side story (about the trash)

On June 13, 1890, residents and business owners around the garbage works got together to see what they could do. As they arrived at the home of Henry Heames at 22nd and Fort Street, 70-year-old Sylvester Larned stood on the steps to greet them, inviting them to take a big whiff of the “odiferous air” wafting up from the river on their way into the hall.

Illustration of Col. Larned from an 1893 Detroit Free Press story.

At the meeting, the neighbors aired their grievances with the garbage factory. One said he’d heard that a woman had contracted typhoid fever from the air around the plant. A florist in the neighborhood, Mr. Taplin, said ladies wouldn’t patronize his shop anymore because it smelled too bad. A man named Seth Carpenter said he’d visited the Sanitary Works recently and counted 49 dead dogs and four dead horses on the ground.5 When one neighbor pointed out that Mr. Chamberlain denied that his factory smelled, another replied: “He must be deaf in his nose.”

That night, 100 people signed a petition to the Board of Health, stating that they were “sorely afflicted and our lives imperiled by the fetid, noisome odors, and our property destroyed from the uncleanliness of those establishments which are so obnoxious, filling the atmosphere of the whole surrounding neighborhood with deadly gases.” They asked the city to shut down the Sanitary Works and vowed to take legal action if their civil efforts were not successful.

Headline from the Detroit Free Press about the meeting at Heames’s hall, June 14, 1890.

They weren’t bluffing. In the fall of 1890, the neighbors sought an injunction against the Sanitary Works. A Wayne County Circuit Court judge determined that the garbage works were indeed a nuisance and ordered them temporarily shut down. Lawyers for the Sanitary Works had argued to the judge that the factory didn’t smell bad and that they were working on mechanical improvements to reduce bad odors going forward. In a response to the judge’s nuisance ruling, the company’s lawyers responded that maybe the neighborhood just wasn’t a place where people should live anymore. (!)

It was a relief for the West Siders, but the relief was brief. By the time the weather warmed up again in 1891, the Sanitary Works was back in operation, belching its belligerent gases into the air. (One desperate resident floated the idea of an “aerial sewer system” that would channel the bad smells out of the neighborhood and into some great beyond where they wouldn’t bother anyone. Intriguing!)

That July, Sylvester Larned and his wife Nellie both filed civil suits against the Sanitary Works, suing for $50,000 each for damages caused by the “foul, uncomfortable, disagreeable, sickening, unhealthy, poisonous, prostrating and penetrating stenches, odors, vapors and gases” emitted by the Sanitary Works. Larned alleged in the suit that he was no longer able to work due to his poor health and had lost some $15,000 in income.

A jury ruled against Col. Larned in 1892, unable to determine whether his illness was caused by the sanitary works or some old war injury or just old age.6 But by then, city leaders were committed to finding a long-term solution to the problem of the Sanitary Works, and the garbage in general.

(Look how much this was part of the local discourse: a front-page ad from a local piano dealer, using the garbage works drama as a hook.)

Readers were INSATIABLE for GARBAGE WORKS TAKES! You can take a closer look at the advertisement here.

It wasn’t just the smell. Detroiters complained constantly about the Sanitary Works. They complained that their trash wasn’t collected consistently. They complained that collectors left a mess in their alleys. They complained that the garbage was hauled around town in leaky open wagons that were noisy, gross and, of course, smelled atrocious.

This image of a trash-strewn Detroit alley is from 1911 and when I first saw it, I thought, “wrong era!” but actually … it’s kind of not. Just imagine more rotten cabbage and dead cats in 1890. Via the Detroit Public Library.

When the council renewed the Sanitary Works contract in the summer of 1892, they did so with some conditions. The Sanitary Works was to subsidize the pay of two city-employed “garbage inspectors” who would address complaints about trash collection and assure that residents were sorting their trash correctly and into proper receptacles. For every complaint against the company not resolved within 24 hours, a $10 fine would be issued. (That summer the Sanitary Works racked up $2,400 in fines, which they refused to pay.) The Sanitary Works would also have to build a new garbage works, well beyond the city limits. Ultimately, the company found a site along the Huron River in Van Buren Township, conveniently located on a rail line so the trash could be shipped there on special trash-carrying train cars from Detroit. (The new works were built at French Landing, today a scenic fishing spot apparently, where we should maybe have a little Little Detroit History picnic this summer?!)

Unfortunately for Sylvester Larned, he did not have much time left on this green earth to enjoy the once-again-fresh air in his neighborhood7. In 1892, the Larneds left the Porter House and, after his doctor prescribed a “sea voyage,” Sylvester removed for a time to London to stay with his daughter. Late in 1893, Larned died there, at the age of 73. His obituary in the Detroit Free Press mentioned the garbage saga: “Three years ago his health failed, due, he always said, to the villainous odors emanating from the sanitary works, which plant was erected opposite his old home.”8

As for the Sanitary Works, the company now had to figure out what to do with the 50 tons of garbage it collected a day while their new works was under construction.

Next time: What they did with it.

We will return to the story of the Labadie House soon! Don’t worry Dan!! I just need to write a comprehensive history of 19th and 20th c. waste management first!!!

This footnote could be, may yet be!, a whole separate installment, but to make it snappy, one popular dumping ground was the Detroit River tributary known as Bloody Run, which today is a “ghost stream,” except at Elmwood, where it runs above ground. Otherwise, it is part of the sewer system. Why is it part of the sewer system? For one, to prevent people from throwing their trash in it. It got so bad in the 1890s that the health department hired PRIVATE DETECTIVES to catch illegal dumpers and issue them citations. Also, full circle: in some places where the run was filled in, ashes and street sweepings were used to bring it up to grade.

“but what about all of the city’s other waste,” you might wisely be asking right now. what about the ash waste, and the street sweepings, and the wood scraps, and the tin cans? well, we’ll get to that, okay? eventually.

I need Greenfield Village or something to install a working 19th-century garbage factory — if these kinds of factories worked at all! — because I cannot wrap my head around any of this.

Disposing of dead animals was in fact part of the Sanitary Works remit; per its contract with the city, the company was required to remove residents’ dead pets and livestock. The city’s animal control department also gave dogs it had euthanized to the Sanitary Works for disposal and urged the angry residents of the Bloody Run district to call them for removal of dead animals illegally dumped in the creek.

“Considerable trouble was experienced in securing a jury, most of those called developing pronounced opinions on the subject of odors in general and sanitary works odors in particular,” wrote a reporter for The Detroit News in its coverage of the Larned v. garbage case on Feb. 8, 1892.

The News reported in Larned’s obituary that he had planned to appeal the case to the Michigan Supreme Court, at which point the Sanitary Works settled with the Larneds for an undisclosed “comfortable sum,” noting it was less than what they had sued for.

also, the trash works at the foot of 24th Street didn’t really … entirely … stop. for like, decades. but uh, t/k.

This is just a cemetery sidenote, but there was some confusion over the disposition of Larned’s mortal remains, which the newspapers reported would be shipped back to Detroit for burial. But his daughter had him cremated in London instead, which surprised everyone so much that this was also reported in the papers, I suppose because cremation was kinda new and people thought it was a little weird? Anyway, his cremated remains were ultimately sent back to Detroit and interred at … U KNOW IT … Elmwood Cemetery, near his father and many other locally famous folks and namesakes of streets and models of equestrian statues.