Why doesn't Detroit have a natural history museum?

“The Detroit Scientific Association solicits offers from any person having a large room on the ground floor suitable for museum purposes.”

— Detroit Free Press, 1879

Hand-tinted lantern slide of Dennis Glen Cooper looking at a T. Rex skeleton at the American Museum of Natural History, ca. 1930s. Dennis Glen Cooper Collection, Wayne State University Library Special Collections.

When I lived in Milwaukee, I spent a lot of time at that city’s Public Museum, which became a place of peace for me in ways I cannot totally explain. The museum is huge, but it never feels cavernous; there are many dark hallways and secret-seeming enclosed spaces to explore, ice caves and 1890s storefronts and a walk-in closet full of seashells. As groups of school kids shrieked through, I’d have little private cries in shadowy corners, rest my eyes on the skies and grasses of the old-school animal habitat dioramas.1 Did I learn anything about science or the natural world there? I don’t know! But delight is a balm, and there is so much delight, unforced and old-fashioned, in every corner of this museum. Objects in beautiful arrangements. Untouched 30+-year-old vintage signage that now looks good as hell. A butterfly coming out of a chrysalis. A hidden button.

We don’t have anything like this in Detroit. Did we ever? I’ve been wondering.

Some very early leading Detroiters, Judge Augustus Woodward among them, made a short-lived attempt to organize the Lyceum of the City of Detroit, early in 1819. According to its articles of incorporation, the lyceum would expediently establish a library, a museum, a mineralogical cabinet, an observatory and a botanical garden, but in his “History of Detroit,” Silas Farmer reports that the Lyceum lasted only three years: “‘Died of constitutional disorder’ would probably be an appropriate epitaph,” he writes, giving no quarter, dang.

A half-century later, we find a private natural history collection at the home of a Detroit professor by the name of J.M.B. Sill. By this time, as people of means had become worldlier and wealthier, they had started collecting things, for fashion and for fascination — rock and minerals, bones, shells, preserved insects, birds and animals. Schools started acquiring collections, too, ostensibly as teaching tools, but also because they were cool and prestigious. In 1873, an upstart school in Detroit, some place called Weber’s Educational Institution that probably didn’t last the decade was reported to be acquiring “a full cabinet of geological specimens from Minnesota.” A trade had emerged between scientists and expeditionists, taxidermists and other preparators, auction houses, independent dealers, university professors, home collectors, and, presumably, cabinet makers.

Undated calling card for taxidermist and natural history collections dealer Chs. Lummer, Burton Historical Collection, Detroit Public Library.

But at Professor Sill’s salon, on March 27, 1874, a group of gentlemen scientists got together to talk about building something bigger. On the agenda: What it would take to establish a public natural history and science museum in Detroit.

The charter members of the Detroit Scientific Association were serious guys. Besides Prof. Sill, who would later serve as president of what is now Eastern Michigan University, they included a founder of Michigan State University, the prolific collector Frederick Stearns (more on him to come), and the pioneer geologist and naturalist Bela Hubbard.

Many institution-building moments in the city’s history have been motivated by keeping up with other “world-class” cities and attempting to out-class them whenever possible. Hence: Our vanguard aquarium, our first-rate zoo, our better-than-Chicago’s art museum. And though no natural history museum in the U.S. had grown to a “world-class” scale by the 1870s, many had been established and were beginning to take root, including the American Museum of Natural History in New York City (1869), Ward’s Scientific in Rochester (1862), and the collection that would become the basis of the Milwaukee Public Museum (mid-1850s).

In Ann Arbor, the University of Michigan was working on its own plans for a museum of geology, zoology and botany, based on a collection gathered in the earliest days of Michigan statehood by tragic boy scientist Douglass Houghton and his colleagues on the 1837 geological survey. The university also acquired, in 1838, a collection of 2,600 minerals from Europe. This was before the school had any students or classrooms, as this history of the school’s mineralogical museum points out, so I guess you could say UM had kind of a head start.

The Detroit Scientific Association did not want Detroit to be left behind. They started to consolidate their own collections of shells, birds, insects and fossils while making acquisitions (purchasing a set of fossil casts from Mr. Ward of Rochester himself!) and hosting monthly lectures about flowers, nitrogen, mound-builders, bridge-builders, Darwinism, and some of the philosophical quandaries of the day, like science and the Bible and whether natural history points toward God. (One month they hosted a mind-reader from Galesburg!)

Meanwhile, they searched for a permanent home for their museum. Real estate was a special challenge in this era of rapid development in Detroit. Maybe some small business owners or startup natural historical museum founders reading this today can relate. Detroit’s nascent natural history museum bounced around for years, finding a spot only to be kicked out because some other tenant needed the space, or because the building was coming down for new construction. Over less than a decade, the museum moved from the Moffatt Building to an Odd Fellows Hall to the old Capitol Building to a vacant building at Harper Hospital to borrowed space in the Detroit Medical College building.

In the summer of 1883, a grand opening was held for the “permanent” home of the Detroit Scientific Association’s natural history collection in a former YMCA building at Farmer and Monroe Streets. Several hundred fashionable people turned up for a reception at the museum and were entertained by speeches from association members as well as musical performances and recitations. A reporter described a “neat exhibition” of taxidermized “buffaloes, eagles, foxes, deer, peacocks, monkeys, turkeys, beavers, badgers, storks, snakes, wildcats, porcupines, sea lions, otters and other animals,” as well as “twenty-five or thirty large cases filled with birds, nearly every known variety being shown,” display cases filled with mounted insects, shells and coins, “several cases containing relics of the various wars in America,” and a lion skeleton “admirably mounted by Prof J.M.B. Sill.”

In all, the effect was … world-class. “It may be stated that the museum of the Detroit Scientific association, as a whole, has a reputation among scientific associations of being one of the best in the United States,” the reporter concluded.

This is not the Detroit Scientific Association’s natural history museum, but you get the idea. Gallery of birds in a museum, Central Park, New York, ca. 1871, New York Public Library Digital Collections.

The Scientific Association was supposed to have a 10-year lease in the space. God knows why, just a few years later, we find the collection in boxes again, this time at the Detroit Public Library, with the library threatening to remove them because they needed the storage space.

But by this time, there was a new museum in town — the Detroit Museum of Art, forerunner of today’s Detroit Institute of Arts, which opened the doors to its first permanent building in 1888. Its success got some members of the Scientific Association wondering: Could the new museum to become a center of art … and science??

Fred Stearns, collector of everything

Frederick Stearns was a businessman first. Born in Lockport, New York in 1831, he began his pharmacy career when he was 14, apprenticing with a druggist in Buffalo. In 1855, he took everything he had and moved to Detroit, with “little money, fair credit, high hopes,” as he would later say. The pharmaceutical company he founded here started humbly, in a 12-square-foot back room with a cook stove. By the 1870s, spurred in part by the demand for medical supplies during the Civil War, the Stearns retail pharmacy had grown to become one of the largest and best-stocked in the state.2 But he sold that arm of the business in 1881 to focus on his pharmaceutical manufacturing operation.

Photo of the Frederick Stearns & Co. factory from the Library of Congress. This building on Jefferson Avenue near the Belle Isle Bridge is lofts now.

Then, in 1887, Frederick Stearns retired3 and devoted the rest of his life to traveling, studying — and collecting. He spent a year in Japan in 1889-1890, collecting “art objects” and examples of material culture, many of them contemporary and some made for the souvenir trade, including pottery, costumes, textiles and paper craft. In 1890, he donated much of his collection of 10,000 objects, mostly from Asia, to the Detroit Museum of Art. Some of Stearns’ gifts remain in the DIA’s collection: a fistful of “numerous faience and glass beads” from Egypt, a piece of “Chinese paper,” an adorable cache of origami paper frogs. An old museum bulletin from around the time of Stearns’ donation suggests a gentle perplexity, even while praising the benefactor: “There are many pieces, unimportant in themselves, which in a collective sense are of the greatest value.” OK, sure!

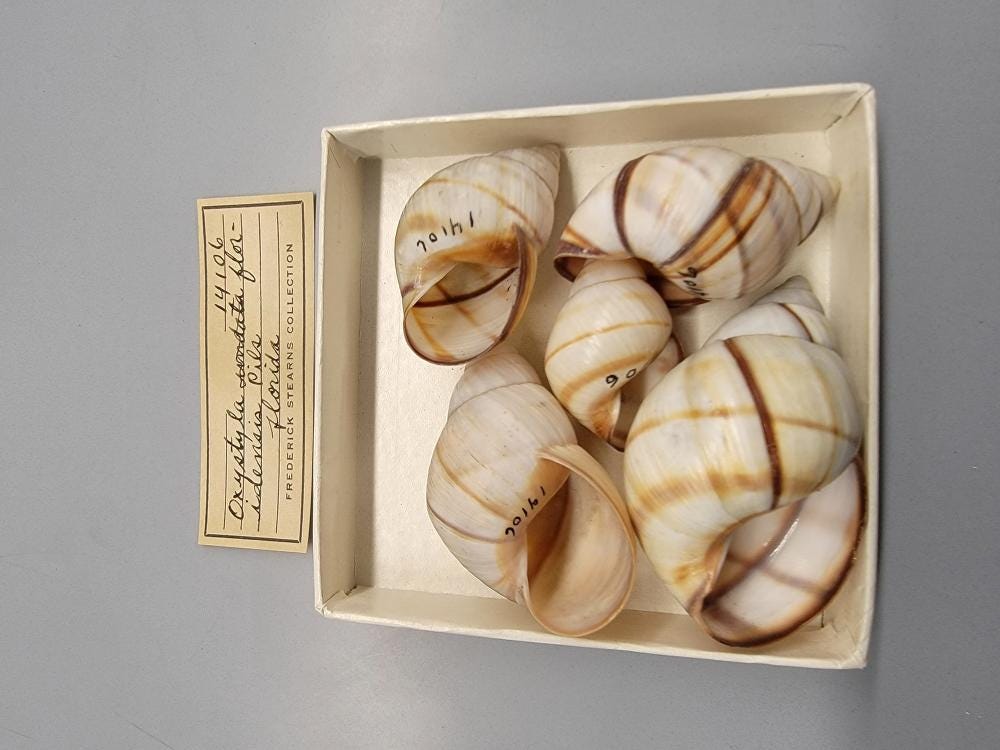

Stearns also added to his natural history collections in Japan, mollusk shells in particular. (I’d love to learn more about the role in this collection played by a Japanese man Stearns employed to travel the country on Stearns’ behalf.4) Stearns worked with Henry A. Pilsbry, a malacologist so productive he was a “veritable institution” unto himself, to publish a catalog of the marine mollusks of Japan based on his collection.

Illustrations from “Catalogue of the Mollusks of Japan,” written by Henry Pilsbry of the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia in collaboration with Frederick Stearns.

But what Stearns may be best-known for today is his huge collection of musical instruments, which Stearns donated to the University of Michigan in 1899. In a centennial history of the Stearns musical instrument collection, UM professor James Borders argues that Stearns thought of this collection as a natural history project, that he was interested in how Darwin’s theory of biological evolution might apply to how musical instruments were developed and improved across human history. Again: OK, sure! The Stearns collection includes a lot of novelty instruments and “contraptions” (look at this walking stick that has a violin inside of it!) and also a not-insignificant number of frauds. But these seem to have made the collection more interesting, educationally, over time.

It seems to have been Stearns’ idea to make a proposal to the Detroit Museum of Art during its first major expansion in 1894: Would the Detroit Museum of Art lend some space to the Detroit Scientific Association, if the association would help pay for the expansion? The museum’s leaders agreed, and a wing of the expanded art museum included space for the natural history collection. Under the terms of the deal, the Scientific Association got a 10-year lease at the museum, but the idea was for the association’s collection to ultimately be donated to the art museum. Perhaps this suggests a lack of long-term thinking, or maybe it shows how sick the Scientific Association was of trying to make its own science museum dreams come true.

The old Detroit Museum of Art on Jefferson Avenue, briefly home to a natural history museum too.

Stearns had an ally in museum director Armand Griffith, who did not have any scholarly training or museum experience; he was working at an art supply store before the museum hired him to lead it. In his 1991 history of the Detroit Institute of Arts, William H. Peck underlines a conflict between Griffith and his museum of “curiosities” — classical paintings comingled with the bird eggs, skeletons, shells and tourist bric-a-brac from Stearns and the Scientific Association — and some of the more serious art collectors of that era, especially Charles Lang Freer, who refused an invitation to join the museum’s board of directors and later donated his major art collection (including James Whistler’s Peacock Room) to the Smithsonian.

Griffith did much to popularize the art museum, building an auditorium and hosting a beloved illustrated lecture series, but he was forced out in 1913, faced with mysterious “unprintable” “serious charges.” The museum was already planning for its move to a new building on Woodward Avenue and refining its mission; a refreshed acquisition policy published in the museum’s annual report in 1914 said the board henceforth would not “accept any gift which has not a distinct art value.” When the art museum opened its splendid new building in the Cultural Center in 1927, it included no natural history displays.

So, what happened to the Detroit Scientific Association’s collections? I realize I’ve worked up to this as some kind of big reveal, a mystery solved!, but as I arrive here it feels more like a footnote and a foregone conclusion: They’re mostly at the University of Michigan, which holds from the Scientific Association the Stearns mollusks and minerals5 as well as a large collection of freshwater and land mollusks collected by Detroit lawyer Bryant Walker.6 UM, of course, has a terrific natural history museum, recently reopened in a new building in 2019. I guess it just keeps coming back — as it did on the question of Detroit’s early astronomical observatories — to the quirky fact that the University of Michigan is not in Detroit.

Florida tree snail shells (oxystyla floridensis Pilsbry) collected by Frederick Stearns, from the collections of the University of Michigan.

Here’s the kicker: This deep dive into the Scientific Association, extinct for over a century, began because I was trying to learn more about a different short-lived natural history museum in Detroit. I regret to admit this was all a prelude, and that we will skip ahead to the 1950s in a future edition of the Little Detroit History Letter.

The dioramas at MPM are in fact so old-school that some of them are the first of their kind. In the mid-1880s, the museum hired a young taxidermist from New York, Carl Akeley, who imagined he was just taking the job to earn some money for college. But in Milwaukee, Akeley wrote, the challenge of imagining more lifelike and scientifically accurate natural history displays “absorbed me so that I gave up all thought of abandoning taxidermy,” he wrote in his autobiography. Akeley’s first diorama for the Milwaukee Public Museum is still on display.

A footnote to the footnote, but my friend Matt Wild really captured the magic of the MPM — which just broke ground this week on a new building — in this beautiful story for his Milwaukee Record a couple of years ago.

Noted pharmacist and ginger ale king James Vernor began his career as an errand boy at Higby & Stearns, the forerunner of the Stearns Company.

His son Frederick Kimball Stearns took over the business. Frederick Kimball Stearns also owned the Detroit Wolverines, Detroit’s first major league baseball team, during its pennant-winning 1887 season.

Henry Pilsbry worked with this Japanese malacologist whose life story is intriguing! I don’t know if he had any connection to Stearns, but it does shed light on a wider network of collectors in Japan and the work they were doing during this time.

UM’s mineral collection, including those samples collected by Houghton & Co. in the 1837 survey, is now stewarded by Michigan Tech. Field trip!

Walker was an honorary curator of UM’s conchology museum and was on the board of directors of the Detroit Museum of Art when it “accepted” Armand Griffith’s “resignation.” He was also a marine lawyer, known for his skill at serving papers to passing ships, according to his 1936 obituary: “A friend recalled that as a young lawyer, Mr. Walker was often retained by Detroit merchants to collect bills owed by captains of lumber schooners which had stopped here for supplies. After contracting debts, many of the schooners’ masters made a practice of passing Detroit on the Canadian side of the river so that legal papers could not be served on them. Mr. Walker would row to the center of the river and if the vessel he was looking for touched American waters he would board her. He became an expert on the boundary line and often was consulted by navigators.”