A bas relief of Justice graced the entrance of the Detroit College of Law, 130 E. Elizabeth St., dedicated October 26, 1937. Photo courtesy the MSU College of Law.

In preservation circles we have our folk tales, our Homeric songs. Sing, muse, the ballad of the Madison-Lenox, Hudson’s, old Tiger Stadium. There are other demolitions we forget, buildings we struggle to conjure. They don’t all have lessons, or the right dramatic ingredients, or they aren’t part of the collective memory of entire generations of people, like department stores and ballparks.

But lots of demolished buildings are part of the collective memory of a few people — might even be, to some of them, monumentally important and worth remembering.

After weeks of research, I am writing to you today with one such tale: the ballad of the Detroit College of Law. I care about it, in no small part, because of my mom, who graduated from DCL in 1991, its centennial year. By the end of that decade, though it counted among its many luminary alumni the very mayor of the city of Detroit, the college had left the city, and its downtown building was gone.

The thing is, at the time it was demolished, no one considered The Detroit College of Law a minor building. It was an institution and a landmark, one of the big losses of the stadium development era. Today, it’s hard to find a single photograph of it. Why is that? What happened? What does my mom think about it??? Let’s explore.

A law school for Detroit

When the Detroit College of Law was founded in 1891, there was only one law school in the state, at the University of Michigan. DCL’s founders were a group of clerks from attorney’s offices around the city who were independently studying law. As this history of the MSU College of Law points out, that means the school’s first directors were also its students.

From the outset, the college welcomed “all classes, without regard to sex, color or citizenship.” When the first lessons began on January 2, 1892, at 7:00 p.m., the class included a woman, Lizzie McSweeney, and 29 other students whose names were not recorded, including six practicing lawyers, a Black student, a Japanese student, and a pitcher from the University of Michigan baseball club.1

The college first met at the Detroit College of Medicine at St. Antoine and Mullet (today the “fail jail” site, if Detroit Street View has it right). In 1913, the law school and the medical school both needed more space, and DCL moved to the downtown branch of the YMCA, which had opened in 1909. The YMCA ultimately took over financial management of DCL in 1915.2

Turns out, the YMCA used to run several night schools and trade schools for working folks. By 1923, there were 20 YMCAs with evening law schools. Other YMCA schools in Detroit included the Detroit Institute of Technology3 and a secondary school, the Hudson School of Detroit.

The Y was OK for DCL for a while, but space continued to get tight as the school grew apace with the city itself. Detroit’s population had grown from about 205,000 in 1890, the year before DCL was founded, to nearly a million in 1920, about a 400% change. DCL moved again in 1924 to — get this — an Albert Kahn-designed garage building at John R and Elizabeth streets. Still bursting at the seams and running out of friendly neighbors with space to lend, in 1931 the college hired George D. Mason to draw up plans for a stand-alone, purpose-built law school. Finally.

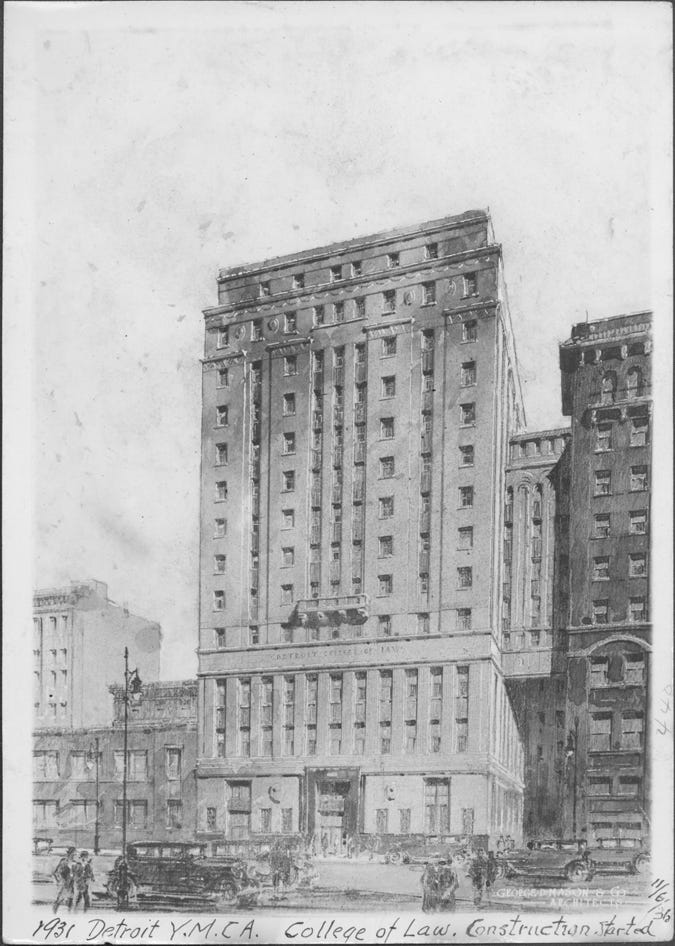

Rendering of the Detroit College of Law by George D. Mason & Co., Architects, 1931, from the Burton Historical Collection of the Detroit Public Library. The rendering shows a building substantially taller than what was ultimately built.

The new building at 130 E. Elizabeth St. opened to students in the fall of 1937. Constructed in an Art Deco style from Indiana limestone with bronze and aluminum trim, decorated with bas relief sculptures by Corrado Parducci of ancestors of law — King Hammurabi, Moses, Emperor Justinian, King John — a DCL trustee called it “probably the finest free-standing structure for legal education in the country.” The four-story structure cost about $400,000 to build.

And that’s where, 51 years later, my mom — a former police officer and single mom of two — walked into a new chapter of her life, in January, 1988. By this time there were three law schools in Detroit: at Wayne State and at the University of Detroit, besides DCL. But my mom — and since she’s my source, I’ll use her name, Joan Ginsberg — said that DCL was the only law school that offered a mid-winter start; she had just quit her job as a police officer, gotten married, and moved, and she wanted to start law school right away. To me, this calls back to DCL’s founding principles: a law school in the city, for all kinds of working people, serving their needs.

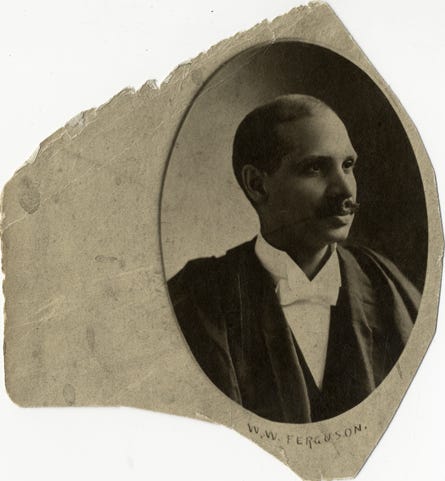

William Webb Ferguson’s class portrait from the Detroit College of Law. From the Burton Historical Collection of the Detroit Public Library.

When she graduated three years later, Joan joined the uncommonly accomplished ranks of DCL alumni. They include Dennis Archer (‘70), who was elected mayor in 1993; Archer, who took night classes at DCL, has said he was motivated to go to law school during the 1967 uprising. George C. Edwards, Jr. took night classes at DCL while he was on the Common Council; he went on to serve on the Michigan Supreme Court. William Webb Ferguson, the first Black member of the Michigan House of Representatives, earned his law degree from DCL in 1897 after his service in the legislature; Charles Roxborough (‘14), elected the first Black Michigan Senator in 1930, went to DCL before he began his political career. DCL graduate William Banks (‘29) founded WGPR, the first Black-owned TV station in the U.S. Geoffrey Fieger, Frank Navin, John DeLorean (!): DCL, baby. Petronilla Joachim (‘23) organized DCL’s tennis team: “This event has given lady aspirants to the bar an opportunity to display their prowess on the courts instead of in them.” She went on to take orders. And before she wrote “A History of Detroit for Young People” — one of my very favorite old local history books — Harriet Marsh got her law degree from DCL.

The Detroit College of Law leaves Detroit

Joan joined the DCL faculty in 1992. Two years later, in the spring of 1994, Mike Ilitch laid out his vision for a new baseball stadium and entertainment district around the Fox Theatre. He was calling it Foxtown, and DCL and the YMCA were both in the neighborhood.

A map of Ilitch’s proposed stadium district published in the Detroit Free Press, March 24, 1994. The Detroit College of Law is number 9 on the map. Next door is the YMCA, number 3.

Plans had not yet placed DCL beneath right field, where it would eventually end up. But the trustees of the college, who already felt they were yet again growing out of their space, could see the writing on the wall. That fall, DCL said it would seek to affiliate with a university — ending its century-long independence — and leave the city for Oakland County.

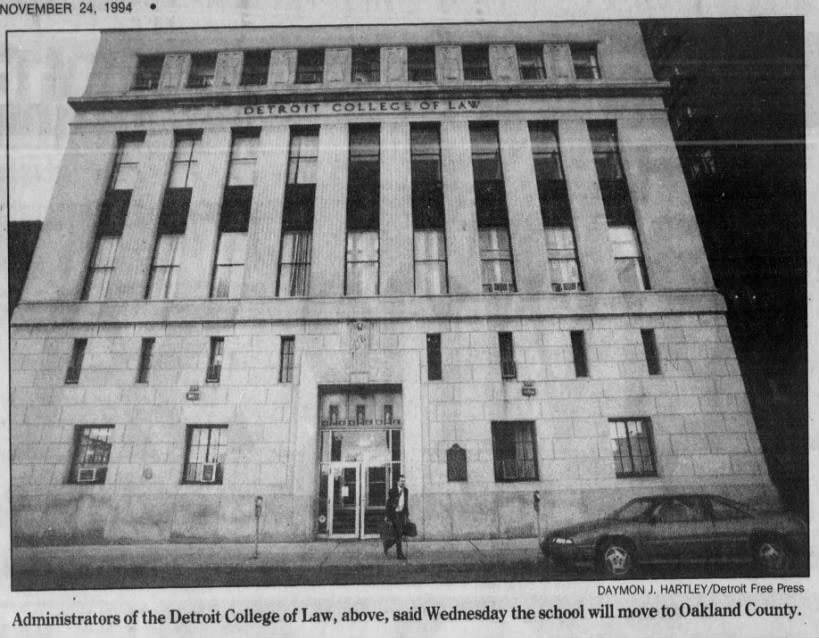

“The move will transfer about 30 faculty and 800 students out of the city,” wrote John Gallagher for The Detroit Free Press on Nov. 24, 1994. “In the larger sense, it deprives the city of another landmark institution that has helped define its image.” The school explored relocating to Oakland University in Rochester, or perhaps to Michigan State University’s satellite campus in Troy.

The move wasn’t just about the stadium, though DCL’s trustees cited the potential loss of its parking lot (lol) as one reason for leaving. It also pointed to the suburbanization of its student body — some 90% of enrolled students lived outside of the city of Detroit — and pressure from the American Bar Association to expand its facilities and affiliate with a public university to keep its accreditation. It would have cost, one trustee estimated, some $25 million to build a new campus in the city, money that the college just didn’t have.

It was a “small outrage” to Mayor Archer, who had campaigned on a message of renaissance and was fighting to keep people and businesses in the city.

Just a few months earlier, Archer had persuaded leadership at WJR not to leave its station in the Fisher Building for new space in Southfield. Though the station had not received any financial incentive to stay in Detroit, Archer had appealed to WJR’s sense of civic duty, and may have pulled some strings behind the scenes.

It was a big win for Archer, and many wondered if he could pull it off again with DCL. He tried. The city at one point offered to sell $15 million in bonds to help keep DCL in Detroit. “Tell me what you need. How can I help? When can I go before your board?” Archer pleaded before a meeting of the House Higher Education Committee in early February, 1995. “I’ve made myself and we’ve made ourselves available. I don’t know what more we can do.”4

It’s hard to know what to think about this, since a big reason the school said it was moving was because of the stadium plan that Archer fully endorsed. Of course, it must have stung for Archer’s own alma mater to reject his efforts to find a creative solution, if that’s in fact what happened. But the president of DCL’s board of trustees, George Bashara, told the same committee that the board had sought help from the city of Detroit for years and “was repeatedly told to ‘wait’ because the Detroit Tigers wanted to build a new stadium in the area.”

When news first broke that DCL was leaving Detroit, Bashara said that an affiliation deal could be years away. But once it was on the table, it happened fast. A deal with MSU was approved by DCL’s board of trustees on Feb. 21, 1995. In the end, the deal went even farther than the Detroit suburbs: DCL would move to MSU’s campus in East Lansing, where ground broke on a new building for DCL on November 27, 1995 — a year and three days after the possible move first made the news.

Joan told me that the mood among her friends and colleagues at DCL was one of resignation: Not everyone loved the idea of leaving Detroit, but what other choice did they have?

Demolition and salvage

Stadium development plans changed a lot in the mid-1990s as Wayne County officials tried to jigsaw out the land strategy and figure out, you know, the money. The proposed new baseball stadium flopped from the east side to the west side of Woodward Avenue and back again. Then, in August 1996, the game changed: Plans expanded to include a new football stadium for the Detroit Lions. This made financing the whole deal easier in ways I do not fully understand! It also made the land acquisition plans a lot more expensive and complex.5

On October 31, 1996, DCL agreed to sell its property to the Wayne County Stadium Authority6 for $3.5 million. The college’s old host, the downtown YMCA, was purchased for $5 million. Other landmarks razed for the stadia included the Albert Kahn-designed YWCA building7, that Kahn garage building that briefly housed DCL, and the Wolverine Hotel. Small residential and commercial buildings were demolished, too, buildings that housed apartments and restaurants and flower shops and cab companies.

Frieze of “Education” from the Detroit College of Law building in Detroit, salvaged and reinstalled at the MSU College of Law. Photo courtesy MSU College of Law.

At what is now called the MSU College of Law in East Lansing, there are remnants of the old building on Elizabeth Street. Some of Parducci’s sculptures are there, including the “Justice” bas relief. A commemorative “DCL Plaza” decorated with those Parducci friezes was dedicated in 2015. Some original Art Deco lamps hang on the fourth floor. It wasn’t all dragged to the landfill.

A “farewell to the building” party was held at DCL on July 17, 1997, as faculty and staff members packed things up. Later that summer, Mike Duggan, then deputy Wayne County executive, said that DCL and the downtown YMCA would be the first two buildings in the stadium’s footprint to be demolished, after the groundbreaking for Comerica Park. Ground broke on October 29, and though I can’t find any reporting about the demolition itself, it would seem that sometime between then and mid-February, 1998 — when a Wayne County official told the Free Press that “everything but the YMCA” had been demolished on the site plan — the Detroit College of Law came down.

This brings us close to the end of our little (and also very long) song. If efforts to save the building were ever organized, I have found no evidence of them. There were other preservation campaigns in Foxtown. Owners went to court to save the Women’s Exchange, which the stadium authority wanted to demolish for a pedestrian walkway. Chuck Forbes fought stoutly to save the Elwood Bar & Grill and the Gem Theatre & Century Club, which were both physically relocated. (The undaunted Forbes once told the Free Press that although moving the Gem was not his first choice, “you could move a pyramid if you had to.”) When huge projects like this unfold, you have to pick your battles, and those battles need champions. When DCL decided to leave Detroit, its most likely champions bowed out.

Joan said that she never felt more connected to Detroit than during her years at DCL. She ate lunch at the Elizabeth Street Café, went to DCL events at the Boat Club and the Masonic Temple, swam laps at the Y and took the People Mover to Greektown and the shops at the RenCen. (I have core memories of riding the People Mover with my mom, in these years.)

Besides the deco details and the interiors I wish I could see today with architecture-appreciating eyes, this is what my mind keeps turning back to: the everyday urban life that, for a century, in a forever changing city, an independent law school in Detroit humbly supported.

The source for this and much else in this letter is “The First Hundred Years are the Hardest: A Centennial History of the Detroit College of Law,” by Gwenn Bashara Samuel, 1992-3.

The YMCA and DCL disaffiliated in 1940, “under pressure from the bar association, which was unhappy with financial interdependence between law schools and noncollege entities, which could divert law-school revenue,” Crain’s reported in 1995, in a very interesting story about a lawsuit over lingering ties between the two entities.

Do yourself a favor and read about how the Kresge Corp. donated its old headquarters to the Detroit Institute of Technology in the early 1970s to say sorry for moving to the suburbs (to their now-doomed corporate Xanadu!) but then the school closed in the early 1980s because it couldn’t recover from the impact of the Iranian Revolution??? It’s a wild ride!

As reported in the Detroit Free Press, Feb. 8, 1995.

The other thing that made things more complicated here were the casinos, which didn’t exist yet, but were expected to exist soon. At one point Harrah’s Casino Hotels spent $23 million for options on four parcels east of Woodward, including DCL.

This is all still very resonant and present as evidenced by Outlier Media’s recent great reporting about this mysterious public body!

Chuck Forbes owned the YWCA; he said in the spring of 1996 that he was planning to redevelop it for apartments, and to reactivate the two theaters inside of it. Some features from the YWCA were incorporated into the Century Club, like the pool tiles that now line the bar.