The time ball wars of old Detroit

A short local tale about the roots of the New Year's Eve ball drop

Hello and Happy New Year! So many of you are new here (welcome!!) that I experienced some performance anxiety as I thought about what to write next and when. Rather than disappear into the woods forever, I challenged myself to write something fast and loose for a special year-end Little Detroit History Letter about the method of public time-keeping that inspired the New Year’s Eve ball drop. Forgive any mess, I had a hard deadline because that shit is today!

If you like this kind of stuff, you might also like some other letters I sent this year about the history of public astronomy in Detroit and the story of wireless telegraph inventor and “human wormhole” Thomas Clark,

Stay tuned in the new year for more little letters to come on the subjects of: eclipses! Natural history museums! More stories from the cemetery! And we’ll see what else! Thanks for being here; I wish you all the luck and magic for the year to come.

-aeb

Before the standardization of time and time zones by railroad companies in the late 19th Century, time was kept locally. How did you know what time it was? I think it was just kind of a vibe. Maybe you set your watch by squinting at the sun at high noon, or when you heard the church bells on your corner ring. But it was said that in Detroit you could walk from one side of town to the other at the top of an hour and hear bells ringing the hour the whole time.

For much of human history, this was not a problem we needed to solve. But railroads found that trying to move people from one place to another, local vibe time to local vibe time, was causing chaos and accidents.

Hence: The development of nationwide standardized time. (To make a long story very short.) But before that, Detroiters, with the help of some geniuses in Ann Arbor, developed a more sophisticated, precise, and ultimately more regional approach to keeping the local time, with game-changing effects for railroads, businesses, and everyday life as we know it.

The Detroit Observatory at the University of Michigan, taken by me at a somehow unflattering angle so go see it for yourself some time.

There’s an old astronomical observatory in Ann Arbor, built in 1854, called the Detroit Observatory. A collaboration between the visionary University of Michigan president Henry Phillip Tappan1 and a group of Detroit businessmen led by railroad lawyer Henry Nelson Walker, the observatory was an effort to give the university (and Michigan by extension) a world-class scientific research facility while also providing cosmically exact time to Detroit businesses and industries. Major funders of the observatory included railroad magnate James F. Joy, shipbuilder John Owen, the merchant Buhl brothers, and several heavy-weight politicians including Lewis Cass, Zachariah Chandler and Henry Porter Baldwin. You can start to see why they called it the Detroit Observatory! So what if it’s confusing!

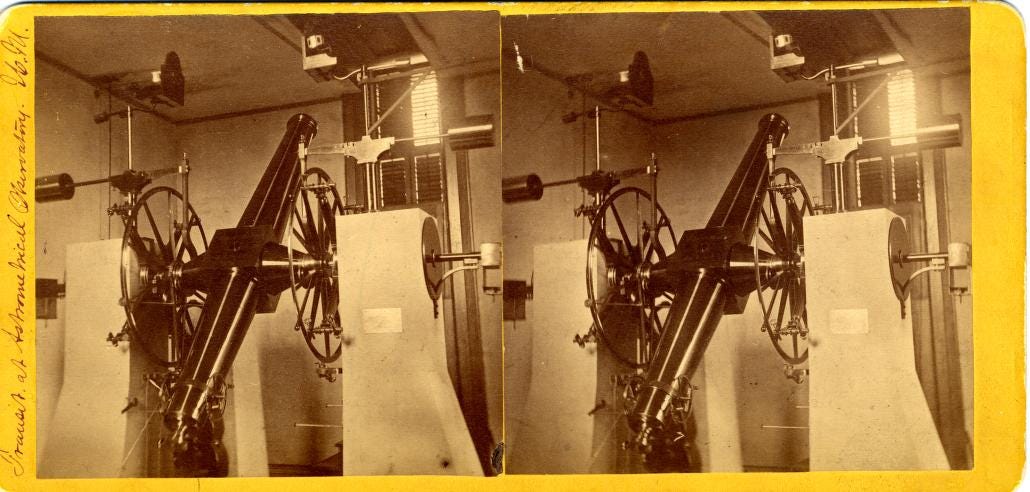

The engine of “Detroit Time” at the observatory was the meridian circle telescope, paid for personally by Henry Nelson Walker and named in his honor. (It still exists in its original mounting and is one of the most beautiful objects I’ve ever seen?) It tracks the position of celestial bodies along a local meridian, establishing time precisely as they pass. (It’s kind of like squinting at the sun at high noon! But better.)

Pre-1900 stereograph of the “Henry Walker” Meridian Circle telescope at the Detroit Observatory, Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan. Doesn’t do the telescope justice but who can resist an old stereoscope.

The telescope’s super-accurate astronomical time was then transmitted over the telegraph to anyone who might be winding up an important clock, like one at a train station, a church, or a municipal building.

Or how about a jewelry store?

In 1863, the observatory reported an arrangement it had made with Martin Smith’s jewelry shop at Woodward and Jefferson to communicate “Detroit time” to the public. This was done by way of a time ball: A big, inflated sphere on top of a spire, connected by telegraph to the Detroit Observatory. When the director of the observatory pressed the key at 5 minutes after 5 p.m. every evening, the ball began to “drop” from the spire on the roof of Smith’s jewelry shop. Whether you were walking by the shop on your evening stroll, or watching from a nearby window, or standing on the deck of your ship in the harbor, you could see the time ball drop and adjust your personal timekeeping device accordingly. (And if you were in need of a personal timekeeping device, well, you might stop into Martin Smith’s jewelry store to peruse their watches and clocks!)

The time ball on the top of Smith’s jewelry shop, from an illustration by Silas Farmer in “History of Detroit and Michigan,” with apologies for the perilously vertical image.

Other cities had observatory-powered time balls, but not very many other cities. The first modern time balls were installed in British port cities, the invention of a captain in the Royal Navy, in the 1830s. The Naval Observatory in Washington, D.C. installed its time ball (which still exists!) in the mid-1840s. The time ball at M.S. Smith’s jewelry shop seems to have been one of the first few anywhere else in the United States, before many more cities caught the time ball craze in the 1870s, including New York City.2

The story could end there, but some 20 years after Smith’s time ball first dropped, a time ball rival entered the ring. In 1882, jeweler R.F.J. Roehm of the Roehm & Wright Company, forerunner of the Wright & Kay Company,3 announced that he would be installing his own time ball on top of his shop on Campus Martius, next door to the old Detroit Opera House.

That September, the Saginaw News reported on an experiment to deliver the time from the Detroit Observatory to Roehm & Wright by telephone, then a 6-year-old technology. “Although the method used was crude, the test was very satisfactory. ... This, as far as known, is the first experiment of the kind in this country for obtaining accurate time at long distance by telephone.”

Roehm’s idea was to take the time from the Observatory and disseminate it via time ball but also by telephone from the jewelry shop to city hall so the municipal clock could be set by observatory time. Roehm — power-hungry? competitive? marketing wizard? clock nerd?? — wanted to take over the Smith shop’s long-cornered market on keeping official “Detroit time.” (Maybe this off-handed comment in the same Saginaw News story explains why: “It would be an unheard-of thing to have a town clock which came anywhere near telling the real time.”)

This was all happening concurrently with the coming of standardized railroad time. Roehm was tied up with the railroads, too; he employed a watchmaker and inventor named Alva T. Hill4, who had invented an amazing “circuit breaker” that would wire observatory time to every telegraph station on the Michigan Central Railroad at 9 a.m. daily, automatically “breaking” whatever else was going over the wires so the accurate time could be delivered to every local station master. The breaker would also trigger a gong to ring at Michigan Central’s depot in downtown Detroit so anyone in earshot could mind the time. (Another, smaller gong at Roehm & Wright’s shop also rang by the same system at 9 a.m. daily). The invention was celebrated at an electronics exposition hosted by the Franklin Institute of Philadelphia later that year.

In 1885, Detroit City Council received competing petitions from Roehm & Wright and M.S. Smith & Co. requesting the official adoption of central standard time — and the privilege of regulating the city clock. The council did adopt central time without much debate, although I could not find a record of discussion as to which jewelry shop should win the day, the council instead turning to some argument over who among them personally disliked the seedsman Dexter M. Ferry the most.

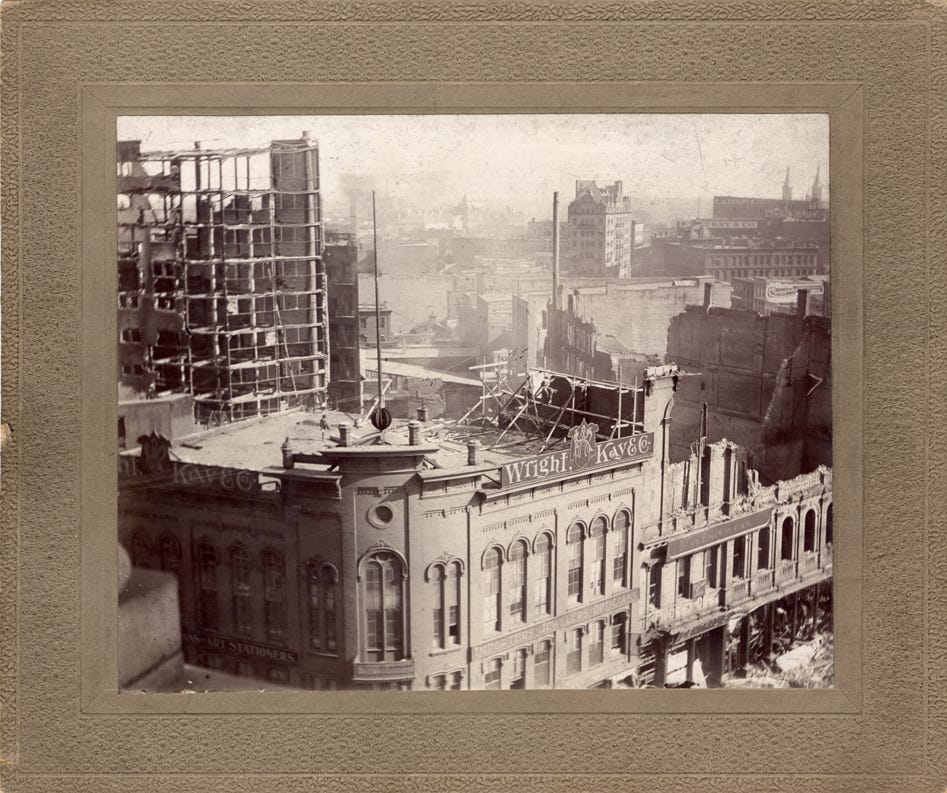

The Roehm time ball was still there in or around 1897, when a fire destroyed most of the block, including the storied opera house.

View of the Wright-Kaye Co. jewelry store and its time ball amid the wreckage, via the Burton Historical Collection, Detroit Public Library.

The Wright-Kay building survived the 1897 fire, a luck of the wind, but Wright-Kay ended its lease in 1910, kicking off years of speculation about the fate of the marquee property. Fred Sanders announced splashy plans to take it over, tear it down and build a fabulous 10-story dessert emporium in its place, but he backed out in 1911, deciding instead to expand his own shop and writing a stipulation into the lease that the property could not be used as a confectionary or ice cream parlor. Eventually the space was leased to a suiting shop; by 1920 it was a Bond’s clothier. Bond’s remained there until the mid-1960s, although by the 1930s the building was either sporting a sleek new Deco facade or had been torn down and replaced altogether. No time ball is to be seen in this 1937 photograph.

As for M.S. Smith, he relocated his jewelry shop in 1884 to the corner of Woodward and State Street. Rather than take his time ball with him, Smith installed a splendid new clock outside of his store, “both a curiosity and a public convenience,” Silas Farmer wrote in his “History”: “... The dials are five feet in diameter and are illuminated at night. There are two life-size figures ... one representing a smith with his hammer, and the other the emblematic Father Time, the figures together symbolizing ‘Smith’s Time.’ ... The clock and its fittings cost $6,000 and was first publicly shown on February 27, 1884. It is the only one of its kind in the United States.” That’s a $200,000 clock by today’s dollar, dang. The old M.S. Smith shop at Jefferson and Woodward was converted to offices and repainted, though I can find no record of the fate of the time ball.

I feel The Time Ball should be the name of a New Year’s Eve cocktail, perhaps even a shot?, in commemoration of this important timekeeping history. If you come up with a suitable recipe tonight, let me know.5

The “John the Baptist of the age of the American university,” according to a source cited on his Wikipedia page, love that

Source for this and muuuuuch more fascinating info than I am including here from a 1980 paper by Ian Bartky, “Naval Observatory Time Dissemination Before the Wireless,” worth a read if this has piqued your interest! And yes, the connection between the time ball and the New Year’s Eve ball drop should be obvious by this point, but the Times Square ball drop didn’t start until 1908 and I think was just an homage to the time-ball and not a repurposing of an actual functional time-keeping time-ball. If any of those words make any sense.

May sound familiar today as the name of one of downtown’s best historic buildings and home to the Wright & Co. restaurant. The Wright-Kay building dates to 1891, but Wright-Kay didn’t move in until after 1910, long past the time-ball era.

FUN FACT: Alva T. Hill’s son Louis C. Hill was the supervising engineer for the Theodore Roosevelt dam.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS: Thanks so much to Austin Edmister at the Detroit Observatory who has been helping me with some research this year and exchanging ideas about local science and timekeeping history with me; this article, “What Time Is It?”, by Andrew Rutledge for the Bentley Historical Library magazine; Patricia Whitesell’s great book “A Creation of His Own: Tappan’s Detroit Observatory”; and, forever, to Dan Austin and his indispensable HistoricDetroit.org (now on Substack!) for the always-essential architectural history fact-checks.