Underwater Underground Railroad

A view of Detroit in 1820 with the steamboat “Walk-in-the-Water” in the foreground. One historian claimed that the first fugitive from slavery to arrive in Sandusky got there on this boat. From the National Museum of American History.

A major inspiration for picking up the newsletter again has been watching my 5-year-old get really into shipwrecks. I admit I have not been a neutral party in this obsession. In the days after Gordon Lightfoot died, I played him “The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald,” and when he asked what the song was about, I gave him the broad strokes. This led to a LOT of questions (“SHIPS CAN SINK??” was one of the first), then visits to the library, some YouTube content of diverse subject and quality, and a billion field trips to the Dossin Great Lakes Museum on Belle Isle.

I am loving every minute of it. The truth is, I have reached one of the main termini of Michigan / Midwest history enthusiasts, and that is shipwrecks. I can feel myself barreling through time toward my destiny, which is writing one of these kinds of books. Sorry but there will for sure be more shipwrecks in this newsletter.

This is a round-about way of explaining what led me to spend a lot time this week trying to learn the fate of the steamship T. Whitney, which from 1859 until 1863 was owned by George DeBaptiste, one of the most prominent Black Detroiters of the 19th Century. Could the T. Whitney have met its end under the water? Might it be there still?

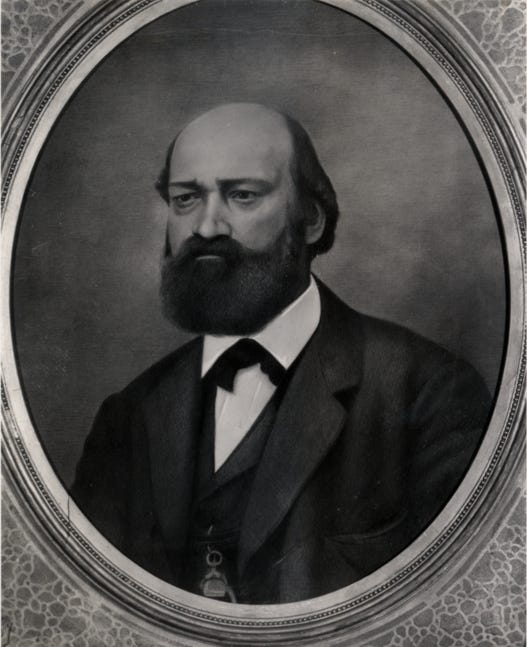

George DeBaptiste. Image from the Burton Historical Collection, Detroit Public Library.

DeBaptiste had come to Detroit in 1846 from Madison, Indiana, where he had been well-known — too much so — for his work helping fugitive slaves from Kentucky make their way across the Ohio River and continue North. But DeBaptiste was increasingly threatened by pro-slavery aggressors in Indiana and there was a price on his head. So he left and came to Detroit, the town known as "Midnight" — the last stop before the dawn of freedom in Canada — and quickly became a leader in an active community of Black abolitionists.

The sidewheel steamer T. Whitney was built in 1853 and named for its first owner, Thomas Whitney of Saginaw. It was sold to Sylvester Larned in 1854, then to the Ives family, apparently in exchange for ownership of their dry dock.

This is not the T. Whitney but a similar ship of the same era, the Arrow, and we get into it in the footnotes.

DeBaptiste bought the T. Whitney in 1859. The ship ran on a route from Detroit to Chatham, Ontario, and later from Detroit to Sandusky, carrying freight as well as passengers, fugitives from slavery among them, who disembarked as free people on the route’s Canadian ports. As a Black man, DeBaptiste was not allowed to hold a captain’s license, so he served as the T. Whitney’s clerk and manager and hired a white captain, Sylvester F. Atwood1, to drive the boat.

In 1863, DeBaptiste sold the T. Whitney to the mariner Michael B. Kean for $8,000. DeBaptiste was busy that year. After helping to organize the First Michigan Colored Infantry Regiment, he became its sutler that fall, following the troops on their campaign in the south and supplying its provisions. After the war, he worked as a caterer and — love this fun fact — won first prize for his wedding cakes in the Michigan State Fair in 1873.2

And what became of the T. Whitney? This is all I know: Not a month after Kean bought it, it was advertised for sale in the Detroit Free Press. “She is staunch and tight ... Price moderate and terms easy. A good sail vessel or freight propeller will be taken in exchange.” No one apparently took Kean up on his offer, and the T. Whitney was converted to a barge. It operated out of Detroit until 1872, after which point there is no record of it.

But there are other ships under the water connected to the Underground Railroad. They include the Morning Star, which sank in Lake Erie near Lorain, Ohio in 1868, after colliding with another ship, the Cortland, which also sank; the May Queen, burned in the Milwaukee River in 1866; the Home, wrecked in 1858, now under 170 feet of water at the bottom of Lake Michigan; and the Niagara, which killed 60 people when it sank in 1856.

There are probably more than we know. Maybe the T. Whitney is among them.

Some important sources for this Little Detroit History Letter include the Clarke Historical Library at Central Michigan University and the book “A Fluid Frontier,” edited by Karolyn Smardz Frost and Veta Smith Tucker and published by Wayne State University Press in 2016, in particular the chapters by Barbara Hughes Smith and Roy Finkenbine. This story about Underground Railroad freedom ships is also really good.

Perhaps not coincidentally, Atwood had experience aboard other Great Lakes vessels connected to the Underground Railroad, including the Arrow, another Detroit to Sandusky steamer on which George DeBaptiste worked for a time as a steward. It was also reported at the time of his death that Atwood had been aboard the Walk-in-the-Water, the famed first Great Lakes steamboat, in 1820; according to Underground Railroad historian Wilbur Siebert, the first known fugitive slave to make it to Sandusky, Ohio came aboard the Walk-in-the-Water from Detroit that year.

A model of the Philo Parsons in the collection of the Dossin Great Lakes Museum from whence I have borrowed this image.

Atwood later was the captain of the Philo Parsons, a ship that was captured on Lake Erie by Confederate raiders in Sept. 1864. The raiders intended to use it to capture the USS Michigan, the only wartime naval vessel on the Great Lakes, and free Confederate prisoners of war from Sandusky. It didn’t work out.

Can’t resist a footnote to the footnote: The Philo Parsons was renamed the Island Queen and converted to run passengers from Chicago to the resort towns of Southwest Michigan by day, then run boxes of fruit from Michigan back to Chicago by night. It burned in its slip during the Great Chicago Fire of 1871.

George DeBaptiste died in 1875 and is buried at Elmwood Cemetery. We visit him on my cemetery tour.