Hello! If you’re new here, welcome! Some context that could be helpful before you read this latest little letter is that I work at a historic cemetery. While I don’t always write cemetery-related history letters, a lot of the time I cannot help it.

This edition is “too long for email” because it has a lot of images in it, but they are a big part of the story, so you’ll want to make sure to download them. You may have to click through to read the entire post; I know that’s annoying, but I think it will be worth it.

One more note: Obviously this newsletter has “ghost” in the subject line, but I promise this is not a scary story. (If you were excited for a scary story, my regrets.) However, it does deal (gently) with child loss, so if you are not in the mood for that today/ever, skip it. xo, aeb

A couple of months ago, a groundsman took me out to see “Ghost Boy.”

He’s not an apparition, but a ghostly visage on a marker: the face of a young boy, rendered in spooky greenish-blue bronze. He looks so serious — hair neatly combed and parted, collar tidy, he hasn’t quite grown into his ears yet. His sweet eyes make the picture a lifelike one; Ghost Boy holds your gaze, as if waiting on you for an answer.

The boy, everlasting in bronze, was six years old when he died in 1906, of pneumonia. His name was Raymond Kushler, and he was the “beloved son of A. & A. Kushler,” the marker tells us.

In years of creeping around at Elmwood, I had never run across Ghost Boy, and no one had ever told me about him. Now I visit him all the time. He’s taught me a lot.

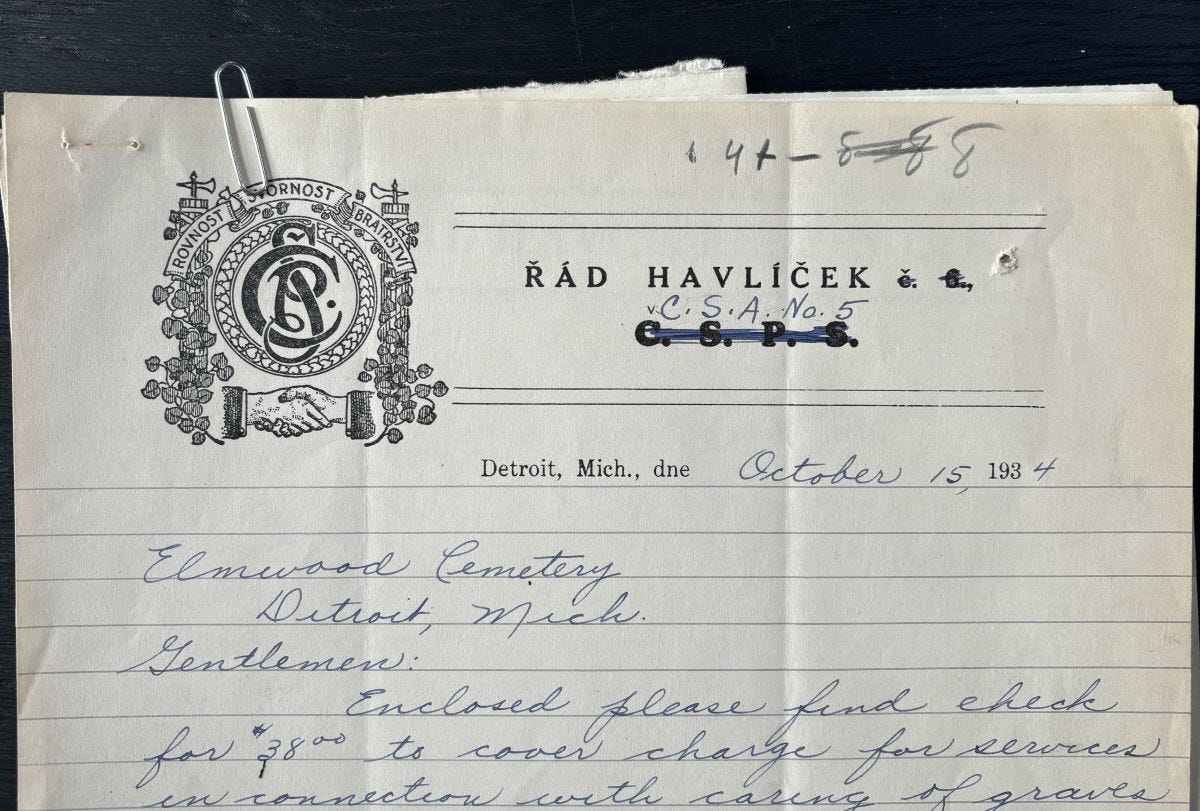

For instance, from the lot card — the cemetery’s record of who owns any given burial lot on the grounds, who is buried on the lot, when and where they were buried there, etc. — I learned that Raymond is buried on a lot that was owned by Lodge Havlicek No. 6, a local chapter of the national Czecho-Slovak Protection Society, the largest Czech-American fraternity in the country. The lodge bought several lots at Elmwood in the 1880s and offered burials there as a benefit to lodge members. Our lot file includes burial slips and correspondence between the lodge and the trustees that span some 50 years (with a beautiful selection of Lodge Havlicek stationery!):

A 1934 letter to Elmwood Cemetery from Lodge Havlicek, recently reorganized as Lodge No. 5 C.S.A. — love the crossed-out name of the old order on the letterhead.

In 1933, Lodge Havlicek No. 6 C.S.P.S. disbanded and was reorganized as Lodge No. 5, at the same time that the national organization reorganized as the Czechoslovakian Association. (This organization still exists today as CSA Fraternal Life!) Not long after that, the new lodge disclaimed ownership of its lots at Elmwood, citing the financial burden of the care fund bills.

The cemetery’s trustees were horrified: “It seems impossible that an honorable society of your type would not only violate this contractual rule, but abandon the graves of the numbers of your lodge who are interred therein,” Elmwood’s superintendent wrote to a leader of the lodge in 1958. “I believe that if your present members thought that the same thing might happen to them in fifty years or more, they might reconsider being buried on any property you might own.”

Revisiting the Lodge Havlicek lots after learning more about them, so much of this story is hiding in plain sight: markers in Czech, even one with “C.S.P.S.” engraved on it. Most are laid flat — often a sign, at Elmwood anyway, that a lot was at some point reclaimed by the cemetery.1 According to Google Translate, this one says “Rest in Peace!”:

But A. & A. Kushler aren’t buried on the Lodge Havlicek lot with their son. Who were they (besides, evidently, members of Lodge Havlicek)? And where are they?

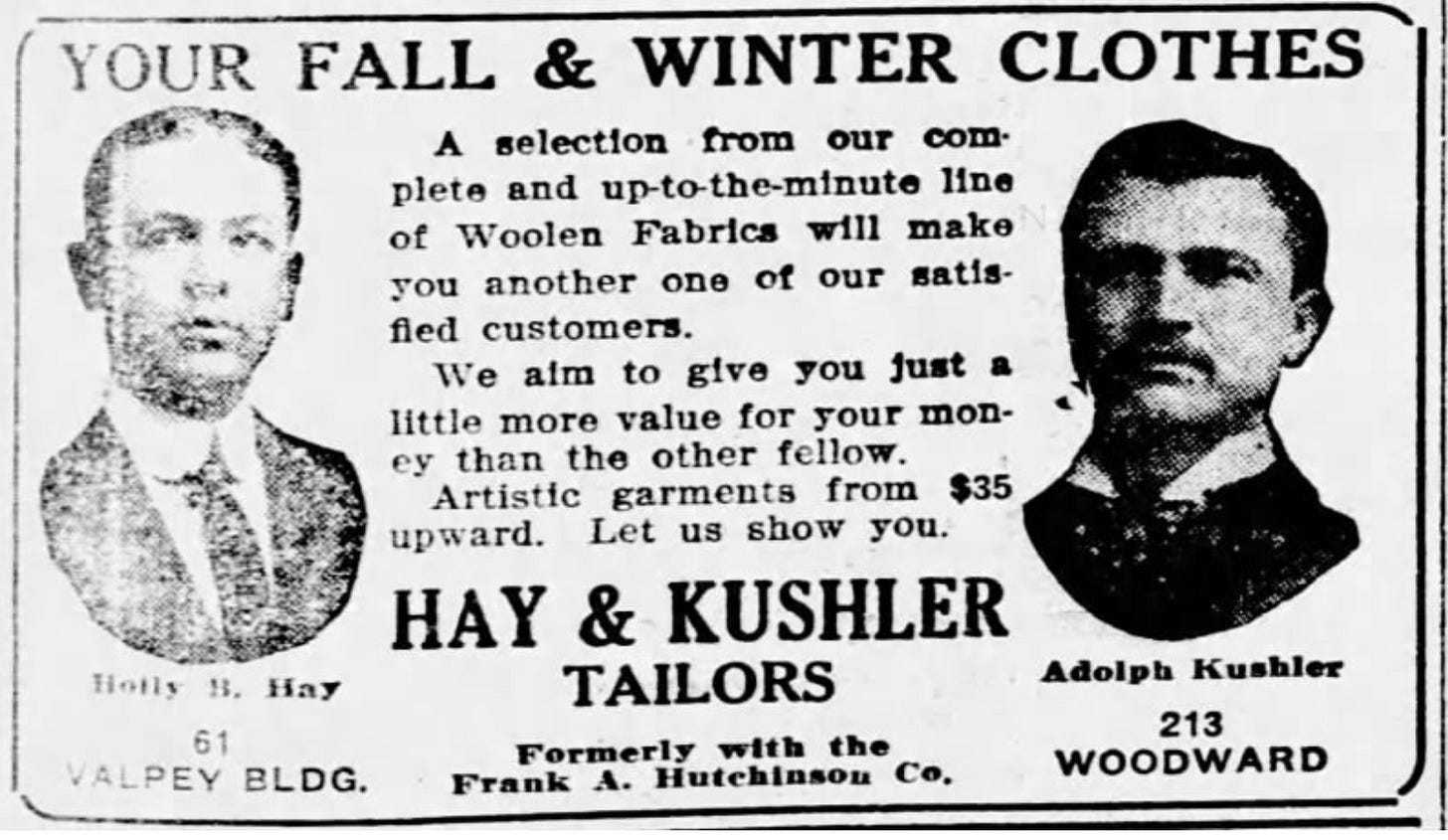

On Raymond’s death certificate we find his parents’ names: They were Adolph and Anna Kushler (sometimes their last name is written as “Kozeluh”). Adolph was born in Detroit, the son of Czech immigrants. His wife Anna was born in Bohemia and had come to Detroit with her family when she was 12 or 13, in the mid-1880s. Adolph was a tailor.

Ad for Hay & Kushler Tailors, Detroit Free Press, Sept. 18, 1910.

Adolph died in 1944, when he was 74. Anna lived another 18 years, until 1962, when she died at 92. They’re both interred in the mausoleum at Evergreen Cemetery in Detroit, 10 miles north of their little son’s grave.

According to Adolph’s obituary, the couple had three other children who survived him: Adolph A., Clarence, and Chester.2 The obituary also mentions beloved Raymond, dead for 40 years, his memory still radiating.

Then I noticed the signature

After gazing at Ghost Boy’s beautiful face for several cumulative hours, I noticed an artist’s mark in the blank space beside his right ear. It looks like it says “Romanelli.”

Romanelli, it’s easy enough to find out, is the name of a family of sculptors in Florence who still have a studio there, founded five generations back in 1777. But would this Czech immigrant family have commissioned their son’s memorial art from a family of sculptors in Florence?

But it turns out that at the turn of the 20th Century — and maybe you are one step ahead of me here — a Romanelli immigrated to the United States.3

Portrait of Carlo Romanelli in the 1903 souvenir program of the unveiling of the Mme. Cadillac tablet.

Carlo Romanelli first appears in Detroit in 1900 in the pages of the Free Press, where we find the young artist working on a model of a sculpture of Antoine Cadillac.4 Over his lifetime, Romanelli became a working artist of moderate renown, carving busts of local luminaries — senators, mayors and bishops in Detroit and Chicago, movie stars (as well as the famous Selig Zoo animals, and some interesting sculptural outdoor advertisements) once he moved to Los Angeles.

Romanelli’s time in Detroit was formative. In 1903, he won a commission to create a bas relief of Mme. Marie Thérèse Guyon Cadillac’s landing in Detroit; it now hangs in the Cadillac Center People Mover Station. He met his wife Lucy Wendlandt here — a love-at-first-sight situation, reportedly — and married her in 1906. He sculpted portraits of Russell Alger, Frederick Stearns5 and Mayor William Cotter Maybury. With Detroit Museum of Art director Armand Griffith, he proposed a group of sculptures of the World Series-winning 1907 Detroit Tigers Sam Crawford, Ty Cobb, and Bill Donovan.6

Romanelli’s relief of the landing of Mme. Cadillac at Detroit, 1903. From the Detroit Institute of Arts.

For at least two years in a row, Romanelli also carved a magnificent butter sculpture at the Michigan State Fair. One year he sculpted a model dairy farm, which is cute and meta. But in the summer of 1908, Romanelli was reported to be working on a masterpiece of the form: “… a model in butter of the city of Detroit, including the business district, the river front, and Belle Isle park. ... This butter model will be eight feet square, and will consume about 1,000 pounds of butter in the making.”7

For almost a decade, Romanelli taught art classes, chain-smoked in his studio, and took long nighttime walks around the city. He was one of Detroit’s best-known Italian Americans, constantly (and stereotypically) quoted for color in the papers, where he is cast as a romantic who loved Dante and cinema.8

Then, in 1909, the Detroit News reported that Romanelli was leaving for Florence and did not plan to return to Detroit. By the 1910 Census, he was living in Chicago — a bigger city with a better market to support his growing studio — with Lucy and their 3-year-old daughter Bianca.

Leaving Detroit and moving to Chicago: We’ve all been there. But we were talking about cemetery art! Sorry: This is all to say that Romanelli was here in Detroit, living and working and going to the movies and smoking a million cigarettes, when Raymond Kushler died.

In the Catholic cemetery on the other side of Elmwood’s east fence is a Romanelli sculpture of the Pieta. Before it was installed at Mt. Elliott in 1908, on the family lot of patrolman Patrick Hally, Romanelli unveiled it at the Detroit Museum of Art.

Here’s the artist’s mark:

The mark makes me confident that Ghost Boy is also a Carlo Romanelli — and the sculpture itself shows us that Romanelli made other memorial art for departed Detroiters during his time here. But just for the thrill of it, I’ll offer one more receipt.

In 1906, the trade paper “Granite, Marble & Bronze” sent a reporter to Detroit to visit its cemeteries and monument shops. One stop was The Vulcan Co., owned by Charles Bovensiep, an iron worker from Germany whose company made bronze doors and grills for mausoleums. At The Vulcan Co., the reporter got a little treat: He got to meet Carlo, who was apparently there on business:

“In the office of this company we met Carlo Romanelli, who had recently furnished this company with a bust in relief to be used in connection with a tablet, one of their many contracts.”

Could it be that the “bust in relief” “in connection with a tablet” Romanelli had just finished was Ghost Boy himself? I had hoped so, but Raymond Kushler died in December, two months after this article was published. Still, once again we find Romanelli working on cemetery art — maybe even for a shop that would hire him again a few months later, to create a tender and terrible portrait of a very loved little boy.

What this also means is that there is more Romanelli cemetery art out there. If you see any other bronze Ghosts while you are out cemetery creeping, you know where find me.

We don’t lay markers flat on reclaimed lots anymore, but we used to, for easier maintenance and lawn-mowing.

Chester Kushler was a charter commissioner when Oak Park became a city in 1945; I believe he later served as mayor.

According to a 1901 profile in the Detroit News, Romanelli came here for work, the hire of an unnamed Detroiter who offered him $8 a day for commercial model work. When Romanelli found out he’d be expected to make a bust a day, he quit. Around 1909, Romanelli moved to Chicago, and then to Los Angeles, where he died in 1947; he is buried at Forest Lawn in Glendale. The basic thumbnail biography of Romanelli that turns up all over the Internet is not correct about where he lived in the U.S. and when. It also inaccurate about Carlo’s parentage: he was not the son of the sculptor Raffaello Romanelli, who was part of the long-standing Florence family of sculptors, but of another sculptor and woodworker named Ferdinand (or Fernando) Romanelli. I don’t know whether or how these Romanellis are related. I read somewhere that Ferdinand was a cousin of Raffaello & co., but I could find so little info about Ferdinand that I really have no idea if this is true or how to verify that. But how about one more fun fact as long as we’re here?: The Dante sculpture on Belle Isle is a Raffaello Romanelli.

This sculpture was supposed to go on top of a huge monument at Woodward and Jefferson Avenues to be erected for the city’s bicentennial in 1901. The monument was never built, apparently due to concern about how many lanes it would take out of the roadway. Here’s a picture of a rendering from the Detroit News that gives you a sense of just how monumental this shit was going to be:

You may remember Frederick Stearns from my story (yet to be completed, sorry!!!) about the history of Detroit’s nonexistent natural history museum.

These were also never created, and that’s too bad for us! I love the concept. I also love this quote from Romanelli: “Who will ever forget the names of Bill Donovan, Ty Cobb or Sam Crawford?” sorry Carlo but we all forgot the name of Bill Donovan.

I would give anything to see the Romanelli butter sculpture of Detroit in 1908.

In fairness, it seems like Romanelli really DID love the cinema. Reported the Chicago Inter-Ocean in 1913: “He asserted that he actually had forsaken the wonderful skies and picturesque environs of his native Florence, the Alps, historic ruins and smiling plains of Italy for the action and energy of the American ‘movies.’ They have given him his ‘touch,’ he says.” The same story reported that he had set up his studio in Chicago’s stockyards district “to study the cattle.” I … love this. A man in love with the dream of the American west!!!!