Hi! Welcome to another occasional edition of the Little Detroit History Letter. If you’re new to the Letter, thanks for being here! I am a local history writer, I work at a local historic cemetery, and while I often write about nothing whatsoever to do with the cemetery, from time to time the twain do meet, as they do today. (Tl;dr, I want you to know about an Opening Day event I am hosting at the cemetery on Friday, and if you just want to proceed straight to more details about that, here you go.)

If sports history is not your thing, please know it’s not the usual bill of fare for the Little Detroit History Letter. Tune in next time when I will probably write something about chloroform poisoning. (Seriously.) But I do sometimes write about baseball. If you like to read about baseball, you’ll find links to some previous baseball history editions of the newsletter embedded below. Have fun! Go Tigers!

“Wahoo” Sam Crawford at bat in Los Angeles in about 1920. From the Los Angeles Times Photographic Collection, OpenUCLA Collections.

A book that I always pick up this time of year is “The Glory of Their Times,” an oral history of early baseball by Lawrence S. Ritter, first published in 1966.1

My favorite interview in the book is the one with “Wahoo” Sam Crawford, who played for the Detroit Tigers from 1903 until his retirement in 1917, winning three American League pennants (but no World Series championship ☹️) along the way.

After his major league career, Sam moved to California to play for the minor-league Los Angeles Angels. He stayed in California for the rest of his life. Although he and his wife had a home in LA, Sam disliked the pollution (and, presumably, the people) and spent most of his time at his cabin in the Mojave desert, in the small town of Pearblossom. (Population in 1957: 550. Population today: About 2,500.) His wife would go months without seeing him.

Sam didn’t have a telephone at his cabin — he went to a bar nearby to use the phone — and he didn’t watch TV. He spent his time gardening, reading, watching the sunset, and never talking about baseball. Ritter spent eight futile days trying to chase down a tip that Sam was living “somewhere between 175 and 225 miles” north of LA. Finally, he ran into him at a laundromat, “a tall, elderly gentleman, reading a frayed paperback.” (“Idly, I asked him if he had ever heard of Sam Crawford, the old ballplayer. ‘Well, I should certainly hope so,’ he said, ‘bein’ as I’m him.’”)

The opening line of Ritter’s interview with Sam to me is an immortal first sentence of American literature: I don’t know how you found me, but since you’re here you might as well come in and sit down.

Crawford’s interview is full of these moments of poetry, most of it not really about baseball at all. Sam talks about how the kids on his block in Wahoo, Nebraska would walk down to the street corner to watch the town’s one electric light — “Just one loop of wire, kind of reddish” — switch on for the night. He talks about traveling the country on sleeper trains illuminated by gaslights, waking up covered with cinders from the coal engine. Here’s how Crawford described an Ed Walsh spitball: “I think that ball disintegrated on the way to the plate and the catcher put it back together again. I swear, when it went past the plate it was just the spit went by.”

When Crawford was named to the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1957, reporters struggled to find him. One LA Times reporter tracked down a Sam Crawford living in a Hollywood hotel. Wrong Sam Crawford, though: “He said wasn’t Wahoo Sam, but knew the old-time major leaguer and was pleased to hear about the selection.”2 When they finally got to Pearblossom, Crawford tells Ritter, his neighbors were surprised to learn about his former fame:

“Nobody around there even knew I’d been a ball player. I never talked about it. So there I was, sitting there in that cabin, with snow all around — it was February — and all of a sudden the place is surrounded with photographers and newspapermen and radio-TV reporters and all. I didn’t know what in the world was going on. ‘You’ve just been elected to the Hall of Fame,’ one of them said to me.

The people living around there — what few of them there were — were all excited. They couldn’t figure out what was happening. And when they found out what it was all about, they couldn’t believe it. ‘Gee, you mean old Sam? He used to be a ballplayer? We didn’t even know it. Gee!’”

Ritter would later described Sam Crawford as “one of my favorite people of all time” and one of his closest friends. Crawford died in 1968, at the age of 88, and is buried at Inglewood Park Cemetery in Inglewood, Ca.

The book is great. Get the book!! But you can also listen to a recording of Ritter interviewing Sam Crawford here. It’s incredible to hear his voice.

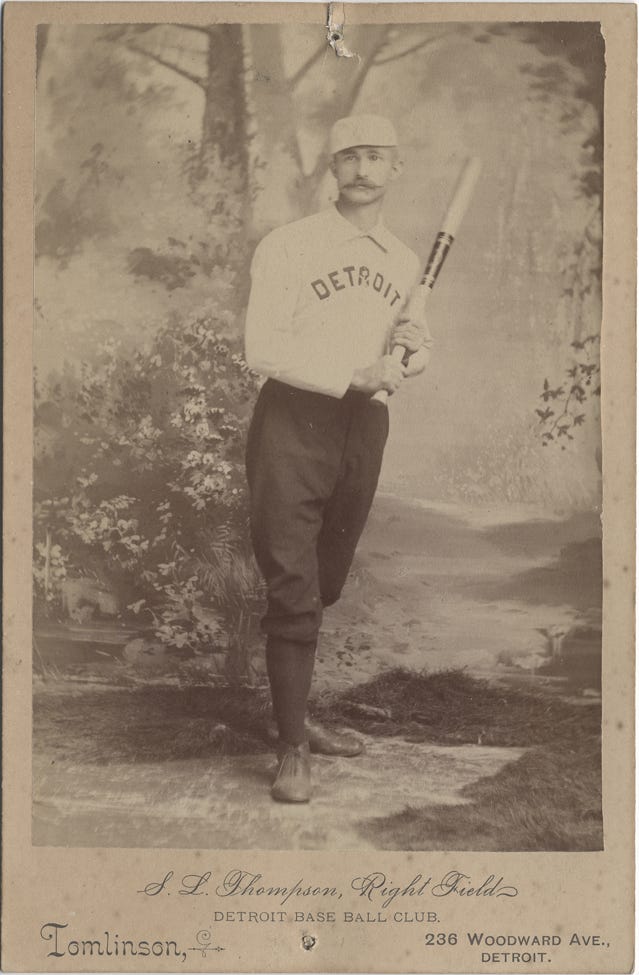

I got carried away (can you tell?) after re-reading Sam Crawford’s interview, but the Tiger I really came here to talk about is Sam (“Big Sam”) Thompson, another great Detroit player of the deadball era. The arc of baseball is long, and Big Sam’s time was even more bygone than Wahoo Sam’s — he’d been dead 40 years when Ritter was criss-crossing the country interviewing old ballplayers.

Base Ball photography was still in its “stand in front of this cheesy painted backdrop” era in Big Sam Thompson’s day. Though this backdrop is actually not so bad.

Sam Thompson was born in Danville, Ind., one of six giant sons of Jesse and Rebecca Thompson, who all played baseball for the local team, the Danville Browns. The story goes that a scout from Evansville came to see the Thompson boys play, but Sam was fixing a roof that day, so the scout paid him $2.50 to quit the job and come play. Sam was picked up by the Evansville team in 1884, then played for Indianapolis in the Western League until the Detroit Wolverines of the National League picked him up in 1885.

“Big” Sam was enormous by 1880s standards. The Wolverines had a hard time fitting him with a uniform; he reportedly split his pants after his first at-bat. He was 6’2”! (I counted 12 of our 26 active-roster Tigers at 6’2” or taller.)

Thompson, along with a roster of the era’s biggest baseball stars, including Dan Brouthers, Deacon White, Ned Hanlon, and my 19th-century baseball crush, catcher Charlie Bennett, carried the Wolverines to the 1887 World Series. Then — another story for another day — the team fell apart. Thompson was picked up by the Philadelphia Phillies, where he played until his retirement in 1898.

During his career, Thompson led the National League in nearly every hitting category. He was the first Major League player to amass 200+ hits and 300+ bases in one season. His career RBI-to-games-played ratio remains the highest in baseball history at .923. And Thompson still holds the Major League record for most RBIs in a single month, driving in 61 runs in August 1894 while playing for the Phillies. I didn’t know this until Bill Dow wrote about Big Sam for the Vintage Detroit Sports blog, but when Thompson came out of retirement to play a brief stint for the Tigers in 1906, he made yet another record as the oldest MLB player to hit a triple. He was 46.3

Sam stayed in Detroit after his baseball career and held a number of jobs in city government, including as a court crier and member of the election board. In 1922, in an election booth at a school in Detroit, he had a heart attack and collapsed, dying at home later that day. As one headline writer expressed, he took his title as National League home run king “to his grave.” His record of 127 career HRs was bested two years later by St. Louis Cardinal Rogers Hornsby.

Big Sam is buried here at Elmwood, where I work. Often last year — especially during the Tigers’ unbelievable playoff run last season — I found myself wandering over to his grave on Section 2 and saying little prayers for good luck to the home team.

This year, I thought maybe other baseball lovers might like to join me in this personal tradition. So I’m hosting a casual coffee-and-donuts hour at Big Sam’s grave on Opening Day, Friday, April 4, 9 a.m. It’s free and will be very relaxed, just a chance to say hello and send up your own prayers for the Tigers. Here’s more info about that.

Two parting fun facts: Sam’s wife Ida loved baseball, and especially Opening Day. She never missed one and over time became an old lady celebrity of the home opener at the ballpark. And: Although Sam and Ida never had kids, Sam’s many brothers and sisters in Danville did. One brother, William, became a baker of some renown. His grandson told me that Sam would have appreciated the donuts! I hope you will, too.

(There’s lots going on at Elmwood this season; I try not to log-roll too much in this newsletter, but if cemetery tours sound like your kind of thing, I invite you to check out our increasingly packed calendar and to sign up for emails to keep up with everything we’re planning!)

More baseball history editions of the Little Detroit History Letter:

The man behind the window

·The 1907 American League champion Detroit Tigers. Not pictured: Philo Robinson. Pictured: Sam Crawford, back row, third from left. Also pictured: A really great baseball dog, front row.

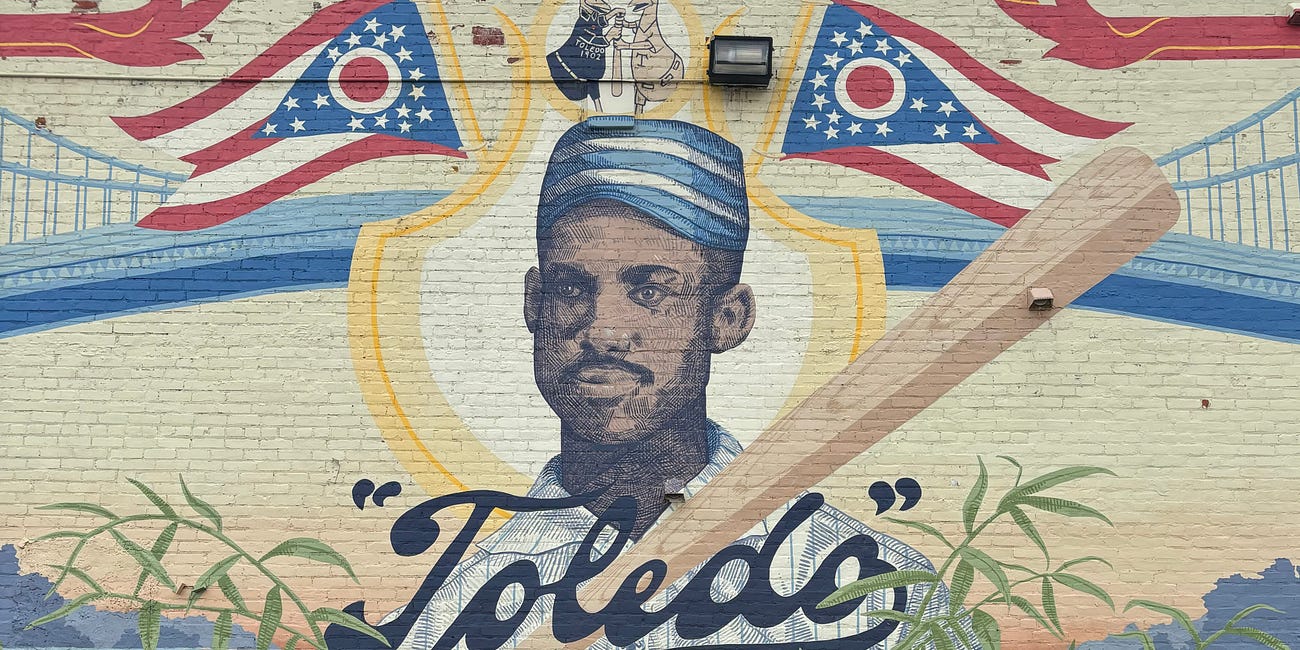

The baseball star on the sidelines of Michigan's first big Civil Rights case

·Mural of Moses Fleetwood Walker in downtown Toledo, Ohio

shout out to Crain’s Detroit Business managing editor and my former boss Michael Lee for recommending this book when I was first getting into old baseball, Mike this book changed me!!!

The Wahoo Newspaper, Feb. 7, 1957

confusingly returning to Sam Crawford for a moment, I was fascinated to learn that he holds the MLB record for most career triples with 309, a record that is considered to be unbreakable! source: this Wikipedia list of MLB records considered to be unbreakable, and you’re welcome for that rabbit hole.