The baseball star on the sidelines of Michigan's first big Civil Rights case

and his swan song game in Detroit

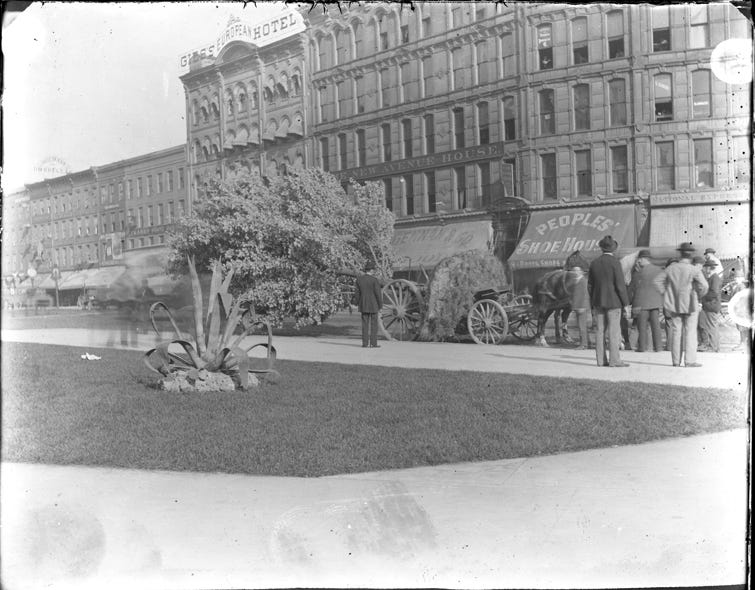

Undated photograph of businesses on Monroe Street in downtown Detroit, with a view of Gies’s European Hotel, left of the New Avenue House. Also, it appears that the horse cart is removing a very large tree? Hmm. Burton Historical Collection, Detroit Public Library.

On a summer afternoon in Detroit, in the year 1889, two gentlemen met for lunch at a restaurant downtown. One was a 32-year-old businessman and real estate investor, the son of a prominent doctor. His friend, visiting from out of town, was one of the best catchers in baseball. They were both Black.

They arrived at Gies’s European Hotel1 and sat themselves at a table dressed in white cloth, with napkins tucked into the water glasses. The men asked the waiter for lunch. The waiter said: “I can’t wait on you here.” He suggested that the men could move to the beer hall next door, which was not a white tablecloth kind of joint.

Assuming rudeness on the part of the waiter, the businessman, a Detroiter by the name of William Webb Ferguson, strode to Edward Gies’s office. Gies and Ferguson, while perhaps not friends, were at least acquainted; they’d been schoolmates. (After a landmark state Supreme Court decision in 1869, Ferguson had become the first Black child to enroll in Detroit’s newly integrated public school district.)

“Mr. Gies, I came into your restaurant with a friend, and I have been insulted by one of your waiters,” Ferguson said, expecting redress.

“That is all right. That is the rule of this house, if you want anything to eat,” Gies replied.

Ferguson told Gies — as a story in one paper reported — that he had $10,000 to spend “seeing if you’re right.”

The discrimination case that Ferguson brought against Edward Gies went to the Michigan Supreme Court, which ruled in Ferguson’s favor in 1890 and established an important precedent: that the doctrine of “separate but equal” in public accommodations didn’t cut it under the state’s constitution. It was one of Michigan’s first major Civil Rights cases and put the state on the national vanguard, six years ahead of Plessy v. Ferguson — the U.S. Supreme Court case that upheld “separate but equal.” Plessy would stand for another 60-some years until Brown v. Board of Education overturned it in 1954.2

Ferguson hired as counsel D. Augustus Straker, who in Gies v. Ferguson became the first Black attorney to argue a case before the Michigan Supreme Court. This case, in a kaleidoscope of ways, made history.

But let’s return for a moment to Ferguson’s guest.

His name was Moses Fleetwood Walker, and at the time of his visit to Gies’s European Hotel, he was a catcher for the Syracuse Stars, a minor league team in the International Association. The Stars were in town for two games at Recreation Park against the Detroit Wolverines as the two teams battled for first place in the league.

Walker, born in Mount Pleasant, Ohio in 1857, had started his baseball career as a student at Oberlin College, where he played on the school’s first intercollegiate varsity team. After a 9-2 victory over the University of Michigan in 1881, Moses Walker and his brother Weldy were recruited to UM. Moses enrolled as a third-year student in 1882 and joined the varsity baseball team as a catcher, becoming the first Black varsity athlete at UM.

A photo of the 1882 University of Michigan varsity baseball team. Moses Walker is third from right on the bottom row. Bentley Historical Collection via Michigan Athletics.

But Moses spent only one school year there. In the spring of 1883, he left Ann Arbor, and for good reason: to play professional baseball, as a catcher for the minor league Toledo Blue Stockings. (Weldy went to play for Toledo, too.) The Blue Stockings won the pennant in the Northwestern League that season and joined the major league American Association the following year. On May 1, 1884, Walker debuted in the majors in a game against the Louisville Eclipse. Most historians of the sport consider this the first time a Black baseball player played major league baseball.

There was not an explicit color line in professional baseball back then, but Walker forced the issue.3 In August 1883, Cap Anson, manager of the Chicago White Stockings, threatened to back out of an exhibition game with Toledo rather than share the field with Walker. Walker was set to sit that game out, but Toledo manager Charlie Morton put him back in to call Anson’s bluff. (If Anson had gone through with his protest, Toledo would have kept the gate receipts.) The White Stockings played that day, but Anson vowed it would be the last time. Three years later, on July 14, 1887, Walker was kept out of an exhibition game between Newark and Cap Anson’s Chicagos, at Anson’s demand. (Newark’s Black pitcher George Stovey was also benched.) That same day, at a meeting of the International League in Buffalo, the league’s members decided that they would sign no more contracts for Black ballplayers.

There was the color line, drawn over in pen.

A final glory in Detroit

Detroit’s baseball fates had changed since the Wolverines won the World Series in 1887. The team had folded, then reorganized as a minor league team in the International Association.

When the Stars came to town for a two-game series in mid-August of 1889, they were the defending champions of the league pennant. But Syracuse was on a losing streak against the Wolverines, and hopes for a repeat championship were beginning to dim.

Then, on August 14, the Stars finally caught a break.

The score was tied 5-5 with one out at the top of the ninth when Walker stepped up to the plate. He hit a ground ball to first base, where the umpire called him safe. From there, Walker stole second, then had his chance when his teammate William “Rasty” Wright hit a single to right field and the catcher “unaccountably let it get away from him” when it was thrown home, according to a report of the game in the Detroit Free Press.

Syracuse won 6-5, its first victory in six games against Detroit, with Walker taking the dramatic winning run that brought the club out of its slump. The Free Press blamed the Wolverines’ loss on the umpire, a Mr. Emslie, for calling Walker safe at first. “The ball (beat) the runner two feet,” the paper argued, describing Emslie’s performance throughout the series as “simply execrable” and biased toward the visitors, a screed that is relatable to Detroit fans of all sports and eras.4

The players had the next day off. Walker had plans to meet a friend in town. We know what happened next.

The Gies Hotel incident was a catalyst, but there was nothing unusual about it, certainly not for Walker, who endured constant disrespect and humiliation. Hotels and restaurants on the road refused to board or serve him; opponents threatened to pull out of games he was set to play in. His own teammate, the pitcher Tony Mullane, would not take his signals.

In the papers of the day, reporting about Ferguson’s lawsuit usually included at least a passing mention of Moses Walker. There were only a few professional Black ballplayers; people were interested in news about them, and Walker was still considered a great catcher, even in the twilight of his career. (Just a month earlier, the Detroit News had described Walker as “the quietest man in the team, but there are none who play better ball than he does.”) But over time, Ferguson’s triumph over Gies’s racism came to take on more historical heft than Walker’s happening to be there that day, and he faded from the story.

The games the Stars played against the Wolverines in 1889 were some of Walker’s last in baseball. Despite his bravura performance in Detroit, he’d had a weak season. The Stars released him on August 23, and that was the end of Walker’s baseball career. It would be another 58 years until Jackie Robinson’s debut.

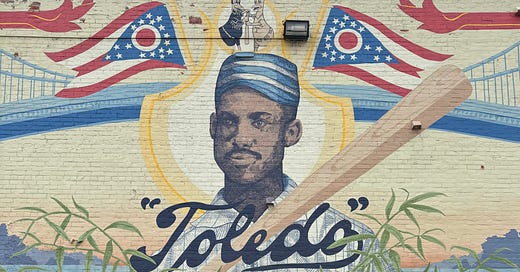

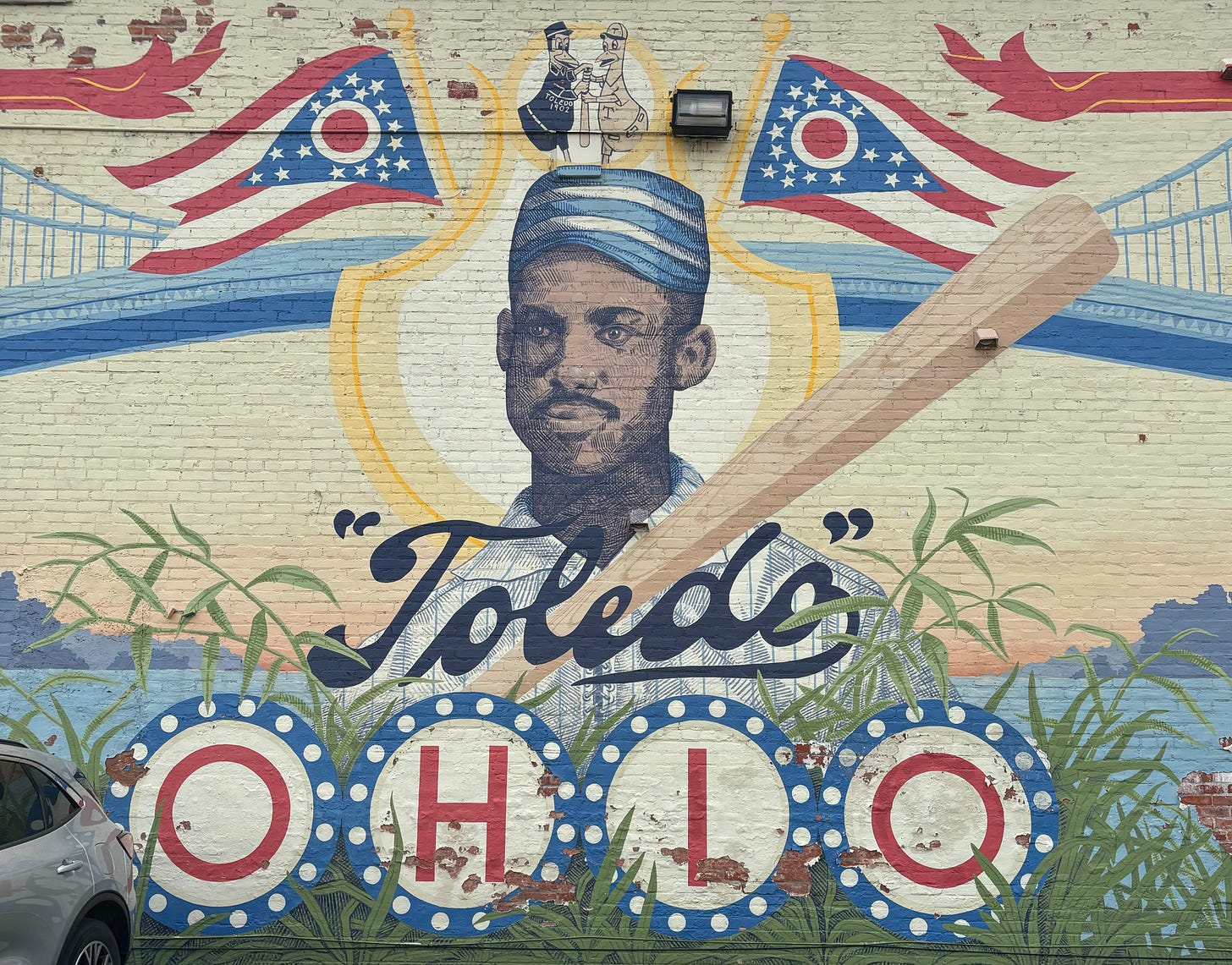

“Island Sanctuary for the Ghost of Moses,” by Natalie Lanese and Douglas Kampfer. 19 S. St. Clair St. in Toledo.

Walker’s post-baseball life is a whole opera. For one, the man owned an opera house. He was also an inventor, edited a Black nationalist newspaper, wrote a back-to-Africa book, and served a year in federal prison for mail robbery. After his death in 1924, his legacy dimmed, then brightened again, as a few persistent historians and researchers reminded the world of his achievements.5 A marker was placed at his grave in Steubenville in the ‘90s. There’s a mural of Moses Walker near the Muds Hens stadium in Toledo, painted in 2017, the same year that his birthday, October 7, became a state holiday. The New York Times gave him an “Overlooked” obituary.

As for William Webb Ferguson, his case accelerated his rise to political prominence. Two years after the Supreme Court’s ruling, he became Michigan’s first Black legislator, serving in the Michigan House of Representatives from 1893 to 1896. His portrait hangs in the state Capitol building; he was named one of the 150 top newsmakers in Michigan history by the Detroit News last year.6

William Webb Ferguson and Moses Fleetwood Walker are both remembered, at least in their local spheres — in Michigan and in Ohio, among baseball and political historians. Finding them together in life — who knows how they even knew each other? — brought both of their stories human dimension for me. Off of the baseball card, out of the top-hatted portrait, into a downtown restaurant in August for a nice lunch.

Remember the Monroe Blocks? That’s where this place was!

Ferguson is buried at Elmwood Cemetery; so is Henry Billings Brown, the Supreme Court justice who wrote the majority opinion in Plessy. So is the Gies family, and so is D. Augustus Straker. Ferguson v. Gies overturned another precedent in Michigan, Day v. Owen, in which the court ruled that it was okay for a steamship operator to refuse accommodation to a Black passenger because it made the white passengers uncomfortable. John Owen, the steamship operator, is also buried at Elmwood. I could do this all day!

In his book “Catcher,” Peter Morris argues that the immense skill and physical toughness required of catchers in Walker’s era — most caught bare-handed — made talent so paramount that race could be overlooked. Catching was a “beacon of opportunity,” Morris writes: “Owners could not afford to turn away a great catcher regardless of his background or skin color, which meant that men of diverse ethnic and racial origins recognized the catcher’s position as a way to be judged solely on the basis of their ability.”

The story does not carry a byline. Mr. Emslie made the headline, though.

Those historians include David W. Zang, author of “Fleet Walker’s Divided Heart,” researchers for the Society for American Baseball Research including Mud Hens historian John R. Husman, and members of the Oberlin Heisman Club, among others.

After his public service he went back to school at the Detroit College of Law!