View of the woods on Belle Isle. Burton Historical Collection, Detroit Public Library.

A century ago, in March of 1924, the Scottish singer and vaudevillian Sir Harry Lauder came to Detroit to perform at the Shubert Theater. He brought with him a cadre of supporting acts — a dancer, a violinist, “two black poodle dogs belonging to the Gaudsmith Brothers,” and Margaret McKee, a professional whistler. The Detroit Free Press described her in its review of the performance as “an attractive girl whose slim throat held a golden treasury of limpid notes.”

Margaret McKee was from Los Angeles. Her father was a harbormaster, her mother a musician, and at their home they had an aviary. As a teenager, Margaret trained at Agnes Woodward’s California School of Artistic Whistling. This sounds very whimsical and twee today, but there was power in a woman whistling in public. “At one time whistling was considered unattractive and even unbecoming in a young woman,” Woodward wrote in the foreword of her book about the art of whistling. “Of late years, however, concurrent with the progress and advancement of art, the potentialities of the human whistle have become most apparent.”1

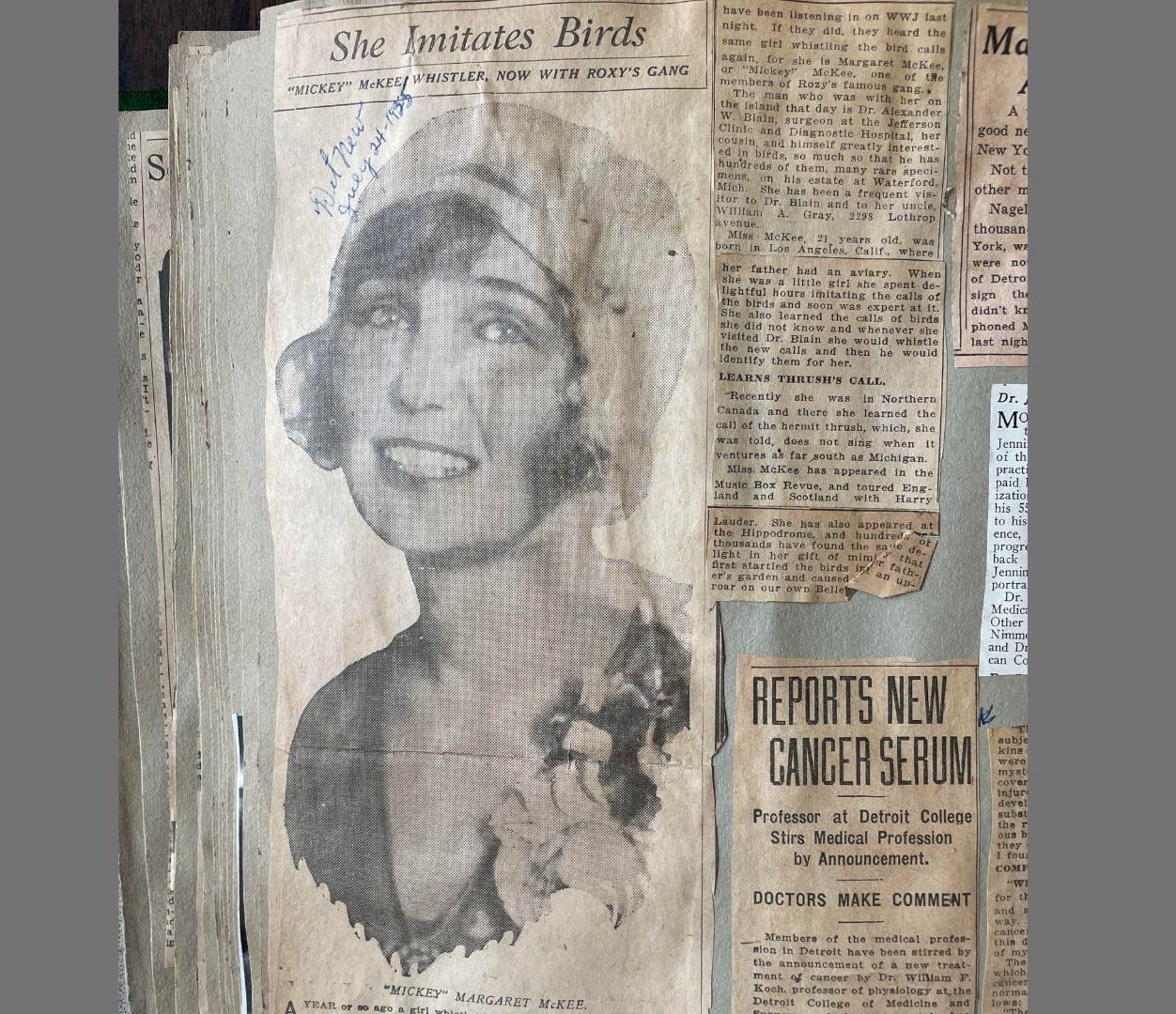

Photo of Margaret Gray McKee from Lyceum Magazine, 1916-17, via the blog Phantom Empires.

Margaret started performing in Los Angeles club houses and churches when she was just a kid. By 1920, she had moved to New York. For a decade she whistled with popular variety shows and touring acts: with Harry Lauder, in Robert Burnside’s “Good Times” at the Hippodrome (where a young Cary Grant made his stage debut as a stilt-walker), and as part of Samuel “Roxy” Rothfael’s gang. She was especially well-known and admired for her bird imitations, and in at least one variety show performed wearing a feathered costume in a cage lowered from the rafters of the theater.2

Roxy’s Gang performed a weekly variety show at the Capitol Theatre in New York City that was broadcast live on radio stations across the country, including our own WWJ. Millions of people tuned in. (“His utter lack of ceremony, his friendliness, his humor and his big-hearted sympathy for shut-ins and other unfortunates” made Roxy uniquely suited for a radio host, the Detroit News assessed in 1925.) It was an incredible platform for Margaret, who sometimes used the stage name Mickey. She performed for President Coolidge and Princess Mary and cut records with Victor and Brunswick. She was big time. For a professional whistler.

In the summer of 1925, Roxy and his gang came to Detroit for a live broadcast from WWJ’s studios at the Detroit News building. (This was just a few years after WWJ’s inaugural broadcast, in one of the country’s few radio stations equipped to broadcast live music.) The gang took a motor car tour of the city and dined at the Detroit Golf Club before their 9 p.m. engagement at WWJ.

Margaret had of course been to Detroit before, but not just as a performer; she had family here. Her maternal grandfather was Andrew Tennant Gray, brother of Mary Gray Blain, wife of landscape architect, cemetery superintendent and Civil War veteran Alexander W. Blain. She was a frequent guest at the Waterford estate of their son, Dr. Alexander W. Blain, Jr. — Margaret’s first cousin, once removed — according to a Detroit News story pegged to Margaret’s 1925 visit.3

Dr. Blain was a surgeon and the founder of the Jefferson Clinic, later known as Blain Hospital, in Detroit. He was also an ornithologist who helped organize the Michigan Audubon Society in 1904, while he was still in medical school. So Margaret and Dr. Blain had birds in common. As a kid, Margaret used to memorize unfamiliar bird songs and whistle them for Dr. Blain, who would help her identify them. And Dr. Blain was with Margaret in Detroit — maybe on that spring visit to the city with Harry Lauder — when she went to Belle Isle to talk to the birds.

“A year or so ago a girl whistled a few liquid notes on the edge of the Belle Isle forest,” the 1925 News story reported. “Instantly the forest was alive with chattering birds.”

“Some birds gave alarm calls, some sang love songs, some raised indignant voices,” the story continued. “And among the wildflowers at the foot of the trees, the girl laughed at them as she teased them with calls of their enemies, with songs of their mates, or scolded the younger birds with rare mimicry of father and mother birds.”

Dr. Blain clipped the story and pasted it in his scrapbook, which is now kept at the Burton Historical Collection of the Detroit Public Library.

Dr. Blain’s scrapbook at the Burton, opened to the page where he clipped the Detroit News story about Margaret McKee.

Margaret appeared in Detroit at least a few more times. She came for a show at the Masonic Temple with Roxy’s Gang in February 1931 and was a guest artist on WJR later that year, whistling with a live orchestra. Her warbles were carried over local airwaves countless times. But, as things tended to go for women of minor celebrity, and as whistling as a musical art form generally fell out of favor, Margaret McKee married and had children, and her fame faded. She died in Los Angeles in 1960, her name misspelled in her obituary as “McGee,” confounding the few researchers who have remained interested in her life and art over the years.

We are lucky to live in the digital age, though, because you can still hear McKee’s work in a few YouTube playlists and in a wonderful compendium of her recordings issued by Canary Records last year.

If you can believe it, this has all been a sidetrack of my still-in-the-works series on Detroit’s history of not having a natural history museum. Dr. Blain is the main character of our next installment, but I only had time for Margaret McKee once I found her story in his file at the library.

So, stay tuned, and until then, think of Margaret on your next walk in the woods on Belle Isle, or when you find yourself idly whistling a tune.

A follow-up about Cartwright’s telescope

“The fate of the observatory … will probably haunt me forever.”

I should know better than to ever write shit like this, which I did in my letter about Detroit’s early amateur astronomers and granite man Oscar Cartwright’s magnificent private observatory at his home on Elmwood Avenue.

Reader Matt O. did some better Googling than I did and found Oscar Cartwright’s telescope at the Whitin Observatory of Wellesley College in Cambridge, Mass.: “The original owner of the telescope was a Mr. Cartwright, an amateur in Detroit, Michigan who bought it ‘merely for his pleasure.’ He paid $2300, not including the cost of additional accessories. … Following Mr. Cartwright’s death, the telescope was sold to Wellesley College in 1904 for $850. It found its current home in 1905 when the original Whitin Observatory was doubled in size.”

Emails to staff at the observatory for comment were not returned! Thank you to Matt for solving the mystery.

Another Woodward School graduate, Marion Darlington, whistled for Disney: “Whistle While You Work” from Snow White and “A Dream is a Wish Your Heart Makes” from Cinderella both feature Darlington’s artistic whistling. Sadly, Darlington is about as well-remembered today as any other professional whistler of her era, i.e. not at all.

As reported by Ian Nagoski in the notes for a Canary Records collection of Margaret McKee’s music, for which I am most grateful.

Blain Island is a WHOLE other story. Not to make this the Little Detroit and Blain Family History Letter, but maybe we will dive into it another time! If you know anyone who lives there or knows much about it, please LMK.